art | architecture | design | digital | gallery | illustration | music | painting | photography | video

Grandi artisti di diverse epoche hanno desiderato immortalare il momento di

un bacio, l’atto più grande del primo contatto di due innamorati, il

momento più dolce di un rapporto, lo scambio alchemico di un desiderio cosi

potente da creare una esplosione di vibrazioni che cancella in un solo

istante ogni altro pensiero. Una tempesta di sistemi nervosi, ormoni, che

non hanno freni ma che desiderano solo perdersi in un amore infinito, dolce

e sensuale.

Il bacio di Tony Nicotra come il bacio di Francesco Hayez, Gustav Klimt,

Amore e Psiche di Antonio Canova, ha una visione quantistica, completamente

nuova, più scientifica ma anche molto romantica e tanto delicata .

Nicotra arresta il momento del bacio, un attimo prima dell'atto in se, un

attimo eterno che rimarrà tale, dove vi è il massimo del desiderio, non un

bacio mancato ma un bacio pieno di ogni energia pronto ad esplodere nei due

amanti eterni.

L’opera di Nicotra deframmenta con la sua tecnica quantistica ogni atto

figurativo della materia come abiti, caratteri somatici, eliminando l’abito

carnale della materia estetica e rappresentando in maniera magistrale ed

emozionante la pura Energia, le vibrazioni dei sistemi nervosi, di quella

energia che solo due grandi amanti possono percepire.

Due amanti che si uniscono in un solo corpo vibrante dove il braccio

dell’uomo avvolge con protezione ed infinta dolcezza la tanto amata. Questa

straordinaria immagine della donna totalmente saldata al cuore del suo

amato in un unico impulso cardiaco, dove il suo volto innamorato piegato

verso il volto del suo uomo, cerca il bacio dell'anima.

Lei legata da intrecci e impulsi nervosi al suo amatissimo uomo, si unisce

profondamente in un solo organismo.

Tony Nicotra is an Italian Artist that was born in Caracas Venezuela on 17 August 1971.

I have always exhibited an insatiable curiosity for the world that surrounds me, and have passionately tried to express my inquisitiveness through drawing and painting. As a young man after finishing my Fine Arts studies, (where by my talents were developed and refined), and with increasing recognition of my artistic skills, I was appropriated into the discipline of restorative art where I worked prodigiously for many years. During this period I won critical acclaim amongst my peers, for successfully restoring numerous important and prestigious Italian works of art and monuments including, The Arena of Verona, The Cathedral of Catania, The Royal Palace of Venaria in Turin as well as the Italian Embassy in Berlin, to name but a few.

Yet despite all these accomplishments, and still driven by my insatiable and ardent desire to fathom the truth and raison d’être of the existence of life, of humanity, and its relationship with its delicate environs, I elected to temporarily suspend my career, to commence a long period of introspective soul searching. I devoted myself exclusively to the search of inner wisdom through the pursuit of knowledge, with a view of liberating the soul within. During this endeavour, I became an avid scholar of various metaphysical and spiritual disciplines, and, despite severe financial constraints and hardships, found myself compelled to pursue a personal and arduous pilgrimage, by walking The Route of Santiago di Compostela, better known as the pilgrimage of St James Path, ending in Santiago Spain.

During this journey I became inspired to study the field of Quantum Physics, and coupled with the knowledge previously gained, I finally found the answers to my deepest questions. Renewed by this personal experience, my quest is to now share my new found understanding and wisdom, through the communicative medium of artistic works, literary prose, and poetry. To this end, I have currently devoted my artistic ability, to the pursuit of rendering tangible and visible, the enigmatic invisible energy fields that constitute the universe and life within it.

My aim is to awaken in all humanity, the awareness and wonder, of the interrelatedness of all that exists, through the interactive dance of fundamental energy forms that constitute both living and non living things. This knowledge is rarely acknowledged, nor experienced by the uninitiated majority. Thus, my mission as an artist, is to utilize my personal wisdom, my faith and my new found perception of self as a singular, liberated and enlightened being, to demonstrate the existence of life as a divine source of permeating energy, constantly pulsating through dynamic and cyclic interactions.

read more »

submission date: 03/03/2020

Patrizia Di Poce, was born in Rome, where she lives and works.

Her artistic course manifests during the years with a creativity in continue evolution, she moves with enthusiasm from painting to ceramics, choosing even common rocks or logs smoothed by sea or river waters as materials for her creations, all different techniques that nurture and develop the sensibility of her artistic expression to finally arrive to marble sculpture.

During the 2006, driven by her quest for an intimate and profound realization, she arrives to Pietrasanta(Lucca) in the heart of Apuan Alps, where she stays on alternate periods in order to realize her creations.

Her marble sculptures are splinters of matter transformed in language.

“ I choose that block of different dimensions (big, medium or small), by instinct, or maybe it chooses me. From this magical encounter, the rhythm of an ancestral dance is born that later manifests with my creations. Like this, that piece become “my piece” because I own its Essence and it reflects my free soul. Presently, to sculpt the marble my way, marble that I feel as a matter of great energy, is simply the realization of a natural talent that I had as a gift. I know I have arrived to the center of my creativity and I feel great. My creations are visible translation of what I feel intimately, a profound perception to which I remain connected and which accompanies me beaming towards the future, with consciousness of a mature woman and joy and enthusiasm of a curious little girl.”

read more »

submission date: 11/21/2019

La competencia ofrece a artistas de América Latina, el Caribe y de la diáspora latinoamericana la oportunidad única de presentar su arte a un público internacional en el famoso distrito de arte de Chelsea, en la ciudad de Nueva York. Los premios (valorados en USD $ 55,000) incluyen la participación en una exposición en la ciudad de Nueva York, participacipación en una feria de arte en Estados Unidos y oportunidades de promoción en línea y premios en efectivo. Un panel de jurados especializados en arte Latinoamericano revisará todas las inscripciones en busca de grandes talentos. El Concurso de Artes Visuales Contemporáneas de América Latina es una plataforma espectacular para promover tu obra a nivel internacional. ¡Aprovecha esta excelente oportunidad para artistas latinos en cualquier etapa de sus carreras! Para obtener más información o para participar, visita http://www.agora-gallery.com/competition/latin-american/spanish

Contáctanos en coordinator@agora-gallery.com o en Facebook.

The Latin American Contemporary Fine Art Competition - June 25 to August 15, 2018

The competition offers artists from Latin America, the Caribbean and the Latin American diaspora the unique opportunity to present their art to an international audience in the famous art district of Chelsea, in New York City. Prizes (valued at $ 55,000) include participation in an exhibition in New York City, participation in an art fair in the United States, online promotion opportunities and cash prizes. A panel of juries specialized in Latin American art will review all the entries in search of great talent. The Latin American Contemporary Fine Art Competition is a spectacular platform to expose and promote your work internationally. Take advantage of this excellent opportunity for Latino artists at any stage of their careers! For more information or to participate, visit

http://www.agora-gallery.com/competition/latin-american

Contact us at coordinator@agora-gallery.com or on Facebook.

read more »

submission date: 5/14/2019

Agora Gallery is pleased to invite artists from across the globe to enter the 34th Annual Chelsea International Fine Art Competition. Selected artists will receive prizes and opportunities that will grant invaluable exposure, boost recognition, and promote career growth.

“The Chelsea International Fine Art Competition has been an annual tradition within New York City’s vibrant art scene for more than 30 years. Artists from around the world can have their work reviewed by distinguished jurors and, if selected, exhibit their work in a major Chelsea gallery. It’s a marvelous opportunity open to all and we strongly encourage artists at every level of practice to participate!”

-Eleni Cocordas, Director, Agora Gallery

The 2019 competition awards are valued at more than $70,000. In addition to cash prizes, other awards include participation in the collective exhibition, featured magazine profiles, valuable PR opportunities, and an honorable mention. A portion of the gallery’s proceeds from artwork sales will be donated to the Children’s Heart Foundation.

“My experience with Agora has been almost a dream come true. I never imagined ever exhibiting in a New York City Chelsea Art Gallery. I thought that would have been the extent of my reward for being selected but I was amazed at how much Agora was committed to the success of the artist… This was absolutely a dream come true. I highly recommend Agora to all artists, especially new and up-and-coming artists. I also reached out to my brother who is a painter and an old high school friend, a photographer. The best thing about Agora was that it reignited the fire in me to continue painting. Thank you.”

-Herold P Alexis Patrick, United States, 2018 Selected Artist

The 2019 Chelsea International Fine Art Competition will be accepting submissions between February 5th and March 12th, 2019. Results will be announced on April 16th, 2019, with the competition exhibition slated for August 10–20, 2019.

Are you ready to take your career to the next level? Apply to be recognized by Agora’s reputable jury. Visit

http://www.agora-gallery.com/competition/ for more information and detailed instructions on how to enter. You can also contact us at competition@agora-gallery.com.

read more »

submission date: 1/8/2019

Siamo in presenza di un autore che sta apportando un contributo autentico. Enzo Marino, il cui gesto rigoroso può essere compreso soltanto guardando molto in dentro, non oltre la materia, ma dentro la materia, non oltre la pittura ma dentro la pittura.E’ proprio dei buoni pittori far vivere nell’opera una luce che sia quelle stessa della loro esperienza, storica e concettuale non meno che percettiva. Enzo Marino infonde la luce umida e blu, inconfondibile e non altrove reperibile, di una particolare area campana disposta sul mare e sotto un tremendo focolaio vulcanico. In questa luce l’esistenza persiste a rischio, è atletica, sfida potenze inumane, sopporta il travolgimento ma non ammette di non guardare avanti. Qui arte significa lotta: lotta per neutralizzare il soffocante statuto fisico delle cose e conseguire nella favorevole luce umida un respiro liberato dai giallori dello zolfo igneo, e così è enunciato il secondo estremo cromatico di questo abile colorista. Il Giallo è citrino, acerbo, bronzeo, dorato, diluito in biancori rosati, è la Terra in sussulto. Il Blu, appartiene alla profonda regione superiore, anticamente denominata «Etere». La comunione del Giallo igneo, terrestre, mutante, ansioso, e del Blu umido, aereo, stabile, costituisce il Verde, la vita. L’inumano si fa sovrumano, il sovrumano si fa inumano. Nel mezzo, sono i Mortali. Essi hanno dei corpi, quei corpi, segmentati da possenti linee di forza, che sono tema costante e centrale di Enzo Marino. Corpi eroici, corpi spirituali, sono in stretto nesso con l’Etere. Vi nuotano, vi si allungano e protrudono con le articolazioni per meglio penetrarlo. Esso risponde loro, sia che vorticando li accetti, sia che si condensi aureolando una testa in forma di trecce o foulard, sia che ne spinga qualcuno al suo bordo estremo per onorarlo consegnandolo a un destino di catastrofe sublime; esso precipita facendo propria l’imposizione necessaria mentre la rifiuta, con gesto di straordinaria tensione.

read more »

submission date: 11/23/2018

Patxi Xabier Lezama Perier is part of that generation of Basque sculptors who were born and raised with the magic of mythology. The gift of the artist serves to help penetrate the domains of the fables, stories and myths so essential for human beings. Their relational dialectic operates as an urgent need for recovery through the mediation of ancestral transcendental sublimation. Sculptor vitally representative of the symbolic and the mythological in terms of the faces, effects and definitions of such a scenario for the ghosts of the gods, here is the most varied framework for us to dream with his own reality, which he treats and completes as a magical realism. Open and alive artistic experience in the channels of the experimental dimension, with autochthonous figures, myths and legends of the Basque country. His sculpture, as the language of memory, is a luminous communication that contributes to giving a characteristic, personal stamp, which makes it the search for his ancestors.

read more »

submission date: 5/1/2018

Flavio Pellegrini was born in Brescia italy in 1960.

His technical training does not hinder but stimulates his artistic career.

Since 1999, he has followed a mixed path made of technicalities and harmonies, studies and experiments.

The wood is the predominant element in all his works.

The study of the eighteenth century mathematical methodologies enriches his way of interpreting the stretch.

Grooves and etchings patiently researched and regulated by algorithms alternate balancing the form and expressing themselves with the reflection of light. His own recipes harmonize the visual and tactile perceptions of the user.

He works, studies and researches in Flero Brescia Italy.

Nato a Brescia nel 1960.

Ha una formazione tecnica, ma questo non limita la sua estrosa e florida fantasia.

Dal 1999 ha seguito un percorso misto fatto di tecnicismi e armonie, di studi e sperimentazioni.

Predilige il legno come elemento modellabile e lo caratterizza con giochi geometrici.

Sostituisce il tratto generato dal pensiero con incisioni regolamentate da algoritmi matematici.

Ricerca costantemente formule matematiche ispirate a metodologie studiate da matematici del XVIII secolo.

Modella le grafie generate per dare profondità alla scultura.

E' il modo per sintonizzare la percezione visiva e tattile dell'osservatore con le sue sensazioni del creare e del fare.

Lavora, studia, ricerca e sperimenta a Flero (Brescia)

read more »

submission date: 11/17/2017

The Guardians of Time by Manfred Kielnhofer at Public Art Basel. The “Guardians of Time” tour through worldwide museums and exhibitions for many years. The time traveler of the world of Art always seem mystical to their viewers. They walk like monks through the world. No one knows exactly where they will appear next. The Austrian artist Manfred Kielnhofer has created the mystical figures. He has been a freelance artist and worked as a painter, sculptor and photographer for many years. read more »

kielnhofer.com

BASEL, SWITZERLAND: Celebrating nine years in Basel, SCOPE Art Show returns to its pioneering location in Klybeckquai. A wellspring of cultural development for Basel Stadt, SCOPE is the initiator of extraordinary happenings centered on the New Arts District on the Rhine, including the founding of a world class Art & Culture Hall. SCOPE Basel will welcome 85 International Exhibitors alongside 10 Breeder Program galleries, and a selection of Juxtapoz Presents galleries offering a view of the contemporary art market available nowhere else. Exhibitors hail from four continents and over twenty countries including China, Mexico, Japan, Korea, Brazil, Italy, Iran, Russia, Turkey, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, Germany, UK, Spain, and Canada. Following its tremendous success in Miami, SCOPE is honored to present the second edition of Feature | Korea, in collaboration with the Galleries Association of Korea. Sponsored by the Korea Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, this curated section offers a glimpse at the current art trends in Korea and shines new light on the country’s contemporary cultural practice.

read more »

janinebeangallery: booth A13

artists: Inna Artemova, Grigori Dor, Dario Puggioni, Florian Fausch

June 16-21, 2015 - SCOPE Basel, Uferstrasse 40 CH - 4057 Basel, Switzerland

Guido Moretti is the second of three sons, was born on 12 August 1947 at 20 Via Gramsci, Gardone V.T. His father Luigi was a carpenter and used part of the hallway of the house as his workroom. Later, he was able to set up his own furniture factory. Guido much preferred his father's carpenter's shop to school desks.

Guido completed the senior section at the main school in Brescia, where he discovered and was captivated by the beauty of analytical geometry. Then he entered to the Faculty of Engineering at Padua University in 1967. There he created his first sculptures in plastiline. Completed first two years of university, Guido switched to the Faculty of Physics and moved to Milan. In that time he was considering teaching as a carrier. During this time in Milan his sculpting output increased.

In 1973, he settled in Brescia and graduated in Phisics. In the beginning of 1974 Guido started to teach in various schools. He became involved with the Loggetta artistic group and followed various courses in drawing and ceramics. In 80s his creativity knew no bounds: from stratifications he moved on to rotations followed by orthogonal intersections. He created a set of sculptures of orthogonal intersections with various optical illusion shapes and impossible figures.

Photos of his sculptures were published in several Italian magazines. Also his sculptures are part of collections of various museums.

Since 1996 he has worked with Anna Canali's Milan gallery Arte Struktura.

read more »

Guido Moretti Scultore - Architettura Arte Contemporanea

La mostra sarà aperta dal martedì al sabato dalle ore 15,30 alle ore 19,30 fino al 24 ottobre 2015

Le opere esposte, oltre 20, sono in bronzo, plexiglas, nylon, alluminio coloratissimo. Forme spiazzanti realizzate con un originale metodo che talvolta raggiunge la magia dell’illusione e a volte si astrae nella perfezione matematica.

Guido Moretti, nato nel 1947 a Gardone Val Trompia, cresce giocando e costruendo i suoi giocattoli con il legno nel laboratorio del padre. Questo materiale lo affascina e gli consente di sviluppare la propria manualità. Laureato in fisica, diventa insegnante, organizza e frequenta corsi di disegno e di affresco. Inizia la sua ricerca dapprima nel mondo del figurativo poi nel mondo della scienza, e associando le sue conoscenze matematiche e fisiche, trova una sua personalissima linea che lo porteranno ad ottenere prestigiose onorificenze sia in Italia che all’estero. Nel 2004 Pubblica il libro “La Terza Via Alla Scultura” in cui documenta più di venti anni della sua originale ricerca plastica. Il direttore del più grande centro mondiale d’arte illusoria di Los Angeles, Mr. Al Seckel, pubblica il suo libro “MASTERS OF DECEPTION” in cui dedica un intero capitolo al lavoro di Guido Moretti. Partecipa a numerose mostre e fiere d’arte in Italia e all’estero, tenendo spesso anche conferenze sul suo originale metodo di lavoro. Nel 2009 è stato invitato dall’Istituto Italiano di Cultura di Toronto ad allestire un sua mostra personale. Negli anni 2012- 2013 viene onorato nell’ambito della 1° e 2° “grande festa della matematica al parco OLTREMARE di Riccione” con una mostra personale. Attualmente, in Australia, una sua opera il “Cubo-non Cubo”, è usata come oggetto di scena nelle riprese del film “Other Life” dal regista Ben C. Lucas tratto dal romanzo “Solitaire” di Kelley Eskridge, sua estimatrice.

read more »

www.architetturaartecontemporanea.com

Born in Brescia, Giacomo Filippini grew in close contact with art, wandering in the laboratory of his mother, Giuliana Geronazzo, famous artist from Brescia. A vantage viewpoint, a living room where he could understand the movements and personalities that have built the history of contemporary art of Brescia. It is precisely in the workshop in via Quinzano that Giacomo takes his first steps, building his first works with glass. Teacher of art and life Gero was an indispensable starting point from which Giacomo began to build his identity. Through time Giacomo experiments new techniques, including ceramics and raku. Finally, the first sight with iron. First is the iron combined with glass. The strength of iron is opposed to the more fragile exists in nature fascinates Giacomo. The antithesis is the synthesis of these works: energy versus frailty, the metal that does not leave pass light against the transparency, the colour black approached with which glass is painted . The figure of Giacomo in the contemporary artistic scene, however, is defined with his iron works, which are also the biggest part of its production.

read more »

www.architetturaartecontemporanea.com

Sculptress and painter: born in Bergamo, Giuliana Geronazzo lives and works in Brescia, with her own open art studio. After her early studies and exams at Liceo Artistico of Venice, Giuliana starts her personal quest in matter of sculpture: terracotta, bronze, wood, glass resin, raku and glass are the materials and techniques she is nowday engaged in.

From 1986 to 1988 she specializes with internships in raku and ceramic technique in Faenza, with Prof. Galassi Mariani Cimatti. In 1990 in Germany she attends internships of glass fusion techniques. From 1995 collaborates with Museo Preistorico dell’Alto Mantovano: excavations and teaching activities. In her laboratory and in the museum, where a specific path has been set up, Giuliana collaborates at courses of clay modeling also for hyposeeing and blind people: this project is done with a specialized team.

At present she organizes several didactic projects with schools.

“Under, above and inside glass” is the emblematic title Giuliana Geronazzo uses to present her glass works at Villa Pomini in 2001. Informal works, three-dimensional objects through “contemporaneity of glass”, because glass is only volume and what is enclosed inside is only transparency. Works resulting from a rich variegated journey, where studies and research marked a series of important transitions from painting to sculpture, to ceramic, to glass seen like “ union between painting and sculpture” (Franco Azimonti, Councillor for Culture at Castellanza).

“Glass with its numerous applications allows a further deepening of stylistic sphere…the value of light becomes fundamental; light, expressed through strokes, intrusion, bubbles, bravura of spirals, becomes a kind of renewed brush which works out forms and suggests mind patterns…. abstract installations the Artist seems to better build new expressive solutions in, somehow innovative, but also rooted into her history…For Gero fortune is in her hands…” (Mauro Corradini, art critic – Monograph 2009).

Giuliana is present in international art catalogues. Her works are held at both public and private collections. Her sacred art works are displayed in some churches in Brescia and Milano. Solo and group exhibitions and some art pieces are visible on this website.

read more »

www.architetturaartecontemporanea.com

Documentary exhibition on the occasion of the 450th anniversary of the death of the great Florentine artist.

The exhibition Michelangelo. Incontrare un artista universale, covering the life and work of this colossus for all times, is to be held at the Musei Capitolini on the occasion of the 450th anniversary of the death of Michelangelo Buonarroti in Rome on 18 February 1564. In the heart of the city, in that very Piazza del Campidoglio which the genius of Michelangelo made unique in the world, over one hundred and fifty works, of which around seventy by the Tuscan artist, from many of the leading cultural institutions in Italy and elsewhere, are to commemorate the 450th anniversary of the death of an artist who was so magnificent as to have a lasting influence not only on the arts in Italy but also on all universally known culture.

An exhibition which overcomes the objective impossibility of exhibiting “non-transportable” Michelangelo masterpieces (a prime example being the frescoes in the Sistine chapel) by showing works which can be admired together. These works are in fact displayed, in many cases for the first time, facing each other and side by side in an extraordinary compendium of matchless artistic output, from painting to sculpture and from poetry to architecture, the four genres adopted by Michelangelo, which are to be linked up in nine display sections to focus in this way on the crucial themes of his art. One major example is the extraordinary presence in the exhibition of the great

work of art by Michelangelo in a political vein, Brut, on view alongside earlier classical busts, the bronze Brut from the Musei Capitolini and the Caracalla from the Vatican museum, at last on display in a direct comparison with two works which, in different ways and circumstances, were its inspiration.

The fil rouge guiding visitors to the exhibition is market by a series of thematic “opposites” used to highlight the difficulties of the man and of the artist in the devising and creating of his works: ancient and modern, life and death, the battle, the victory and imprisonment, rules and freedom, earthly and spiritual love. The contrast of earthly and spiritual love, for example, was particularly felt by Michelangelo, both in art and in life. This is demonstrated by a set of drawings and other works inspired by close friendships and elective affinities such as those for Tommaso Cavalieri and Vittoria Colonna. Each theme, as if mirrored, is to be analysed by comparing drawings, paintings, sculpture and architectural models, as well as a highly select choice of signed writings, i.e. letters and poetry, via Michelangelo’s full personal and artistic career.

read more »

Michelangelo. Incontrare un Artista Universale. (Italian) Paperback – 2014

by Capretti E.,Risaliti S. Acidini C. (Author)

Lo staff di Architettura Arte Contemporanea vuole testimoniare e promuovere la cultura dell’impulso estetico ponendo uno sguardo incrociato nei vari ambiti disciplinari del campo visivo ed architettonico. La galleria, luogo di eventi non di silenzi, è uno spazio non unicamente espositivo ma un’agorà contemporanea dove vivere e far crescere l’emozione che l’arte in tutte le sue contaminazioni esprime. Punto dove si espongono artisti famosi ed emergenti con carattere, dove artisti e collezionisti possono trovare la loro collocazione ideale. read more »

architetturaartecontemporanea.com

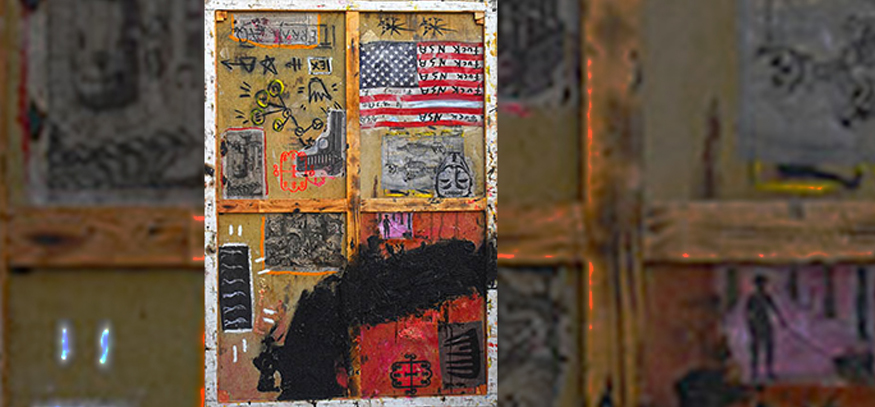

Max Weinberg

Max Weinberg (86!) wurde 1928 in Kassel geboren. Seine Eltern flohen mit ihm und seinen Schwestern vor den Nationalsozialisten 1933 zunächst nach Belgien und schließlich 1935 nach Israel. Dort verbrachte er das erste Drittel seines Lebens und nach Abschluss des Kunststudiums kam er 1959 mit 31 Jahren nach Frankfurt am Main.

In Weinbergs Werk treffen das Irrationale und Rationale, das Impulsive und das Kalkulierte, das Chaos und die Ordnung aufeinander. Seine Kunst ist unberechenbar, ordnet sich keinen Trends unter und bezweckt, der Phantasie neue Spielräume zu öffnen.

Ruben Talberg

Ruben Talberg wurde 1964 in Heidelberg geboren. Er lebt und arbeitet in Offenbach am Main. Talberg ist Pataphysiker. Die Pataphysik ist eine Teufelskreis, in dem die schwefeligen Zeichen und Metamorphosen des Rausches verrückt geworden sind, ohne daran zu glauben. Sie entwickelt sich in einem parodistischen Universum, da sie die Resorbtion des Geistes in sich selbst ohne eine Spur von Blut ist. Jean Baudrillard.

The “wrong” side of the canvas becoming the “right” side. The material depth of wood, carvings, other miscellaneous textural and textual inscriptions. The big black scratch signature dipped in the pen of ashes (an imprint of tar). Beyond the visual to the tactile. Art of great significance for semiotic graffiti- style resistance against global capitalism and finance. Alan N. Shapiro, New York / hfg Offenbach.

13. April - 31. Juni 2014

Eröffnung am Sonntag, den 13. April 2014 - 14:00 Uhr

About Talberg Museum

The Talberg Museum was founded 2011 and considers itself as a long-term investment into the cultural landscape of the Rhein-Main area, a high-carat complement with regards to contemporary art.

Paramount is TAMU’s task to preserve, to explore and exhibit the art of Ruben Talberg, The TAMU sees itself as a permanent autonomous zone of dialogue which manifests itself through temporary exhibitions, permanent exhibitions and events. Special exhibitions are planned with regards to contemporary Israeli (Jewish) art. The building itself dates back to 1891 when Carl Kraushaar opened a carpenter's workshop. He died in 1939 as his son-in-law Carl Salzmann took over the firm. In 1944 the structure was completely bombed out like the rest of Offenbach. After the war it was gradually rebuilt from the ashes and 1951 on its 60years jubilee Salzmann could reopen his carpentry here.

About Ruben Talberg

Multiple media sculptor and contemporary artist, based in Offenbach/Germany and Southern France. The German-Israeli artist creates abstract works from various materials with hidden references to alchemy, Kabbalah etc. Website features biography, press, photo galleries and contact information.

read more »

The shoes symbol of travel, but most of our introspective journey every shoe is a partial portrait of the wearer, a clue to his personality. The shoes as occasionally silent witness of our lives, our expectations, our identity obvious and hidden.

The shoes as a message sometimes obscured even to those who possess them, but ready to read those who can "drive".

The question I have asked is : the shoes are the diaphragm that separates us from the ground, protection from bad roads, but mostly because just that pair of shoes among 100 others?

For everyone the answer that best fits him.

When, 10 years ago, I found in a junk shop some forms of shoes in walnut-1950s, could not resist the urge to withdraw en masse despite not having the slightest idea what to do. What struck me was that on every pair of shoes was hand-written name of the person for which they were produced. This prompted me to imagine the life, character, inclinations belonging to the owners of those objects useless. The thought that these people have left behind a small memory, must have unconsciously touched my imagination.

After a decade I have had the desire to create for them a new pair of shoes, starting from their own forms and inspired by the themes of our daily lives.

Points of view

There are moments that leave us changed. Seemingly distant events that weave the web of life in our unconsciousness. Only later, passing over, we can discover the dense network that bound them. Three images of its history, a single framework: that's how I play the HARMONY OF A PASSAGE OF LIFE.

The images, assembled with great care, will move in a continuum of sequence able to recreate the excitement of the story, still alive every time you look with careful eyes.

About Angelo Franco Bartoli

Born in Monza on 11 .11.1967

Thanks to his grandfather a painter and a sculptor and his mother a painter he has been in contact since childhood with the art world. He has likened taste and techniques he then refined over time, developing a personal expression that has moved into his versatile artistic activity which includes photography, set design, painting, sculpture and interior design.

Over time it has developed a very personal ability to mix materials, with preference for those of recovery, to create objects and installations as expression and communication of its conceptual view of the surroundings.

Currently, in addition to the collaboration with manufacturing companies in various sectors as industrial designer, he continued his daily activities experiencing the development of innovative techniques for the use of industrial materials in the field of art.

read more »

submission date: 5/11/2014

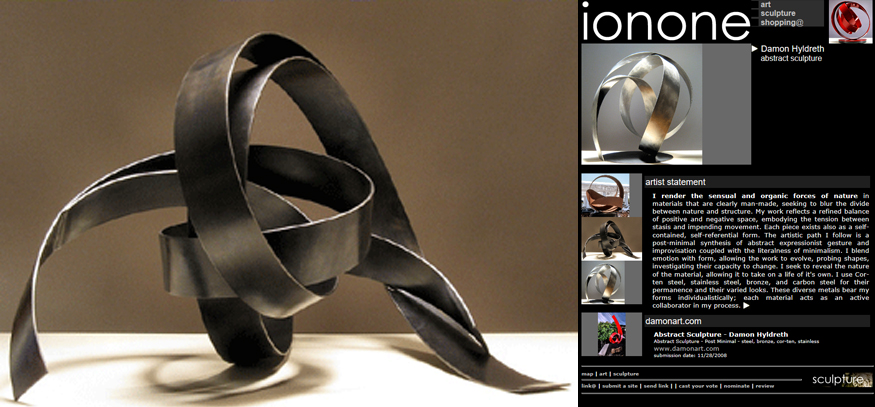

I render the sensual and organic forces of nature in materials that are clearly man-made, seeking to blur the divide between nature and structure. My work reflects a refined balance of positive and negative space, embodying the tension between stasis and impending movement. Each piece exists also as a self-contained, self-referential form. The artistic path I follow is a post-minimal synthesis of abstract expressionist gesture and improvisation coupled with the literalness of minimalism. I blend emotion with form, allowing the work to evolve, probing shapes, investigating their capacity to change. I seek to reveal the nature of the material, allowing it to take on a life of it's own. I use Cor-ten steel, stainless steel, bronze, and carbon steel for their permanence and their varied looks. These diverse metals bear my forms individualistically; each material acts as an active collaborator in my process.

read more »

On March 1st, 2008, Asher Neiman Gallery made its foray into the art world. While we are a fine art gallery, our definition of 'fine art' is expansive; that is, in addition to paintings and photography, we aim to house, purvey, and promote: hand-made jewelry, sculpture, music, and film. Our artist stable contains an ever-increasing variety of mediums and methodologies. Our gallery takes on a separate identity in the evenings. We host meetings, small corporate events, live music, budding artist showcases, as well as fundraisers for various charities. Asher Neiman Gallery is located in Red Bank, New Jersey, a unique and charming enclave just 5 miles from the Jersey shore and 45 miles from NYC. We're honored to inhabit 16 Monmouth Street, the former location of Art Forms Gallery, a beloved Red Bank landmark for 23 years. "I want to disseminate beauty and to stir the soul of any who are curious, to bring a fine aesthetic to peoples' homes and to fill the gallery walls with spectacular examples of creative spirit in a range of color and form." — Emily Asher Neiman, owner read more »

www.asherneimangallery.com

Born in Corchiano in the vicinity of Viterbo on March 16, 1967. After earning his diploma at the Ronciglione State secondary school specialising in scientific studies, he moved to Rome where he worked for some eight years as a graphic artist at an advertising agency. Always passionately fond of art and archaeology, during those years he also devoted himself to in-depth study of texts and documents regarding the goldsmith’s art in ancient times. Little by little he began to combine experimental activity with theoretical learning with the aim of verifying the hypotheses formulated up until then concerning ancient techniques of working gold. Following innumerable fruitless attempts carefully conducted on the basis of the most erudite studies, Cagnetti tried blazing new trails in research, taking a strictly personal technical and theoretical approach. The first encouraging results thus obtained spurred him to redouble his experiments and concentrate on the application of the methodological procedures elaborated. In 1985 he returned to his birthplace where he began to devote himself to the goldsmith’s art on a fulltime basis under the name of “AKELO.” At this time he first started exhibiting his work at various shows and events. During the course of the next eight years he completed a collection of original jewellery offering proof of his having achieved at last the desired stylistic and technical perfection. His creations aroused the interest of the specialised press, as well as of certain television programmes of a strictly cultural bent. Worthy of mention is an article entitled “ Etruschi, scoperto il segreto dei loro gioielli” (or “The Etruscans, Secret of Their Jewellery Unveiled” that appeared in the Corriere della Sera (29 October 2000) and a guest appearance on “ULISSE” (RAI TRE, 23 November 2000) and “Abenteuer Erde” (HR - Hessischer Rundfunk, 27 April 2002). In 2002 he produced a series of works for Capitalia S.p.A. He currently resides in Corchiano where he continues to pursue his creative activities, including other forms of artistic expression, such as painting and sculpture. read more »

http://www.akelo.it/en/

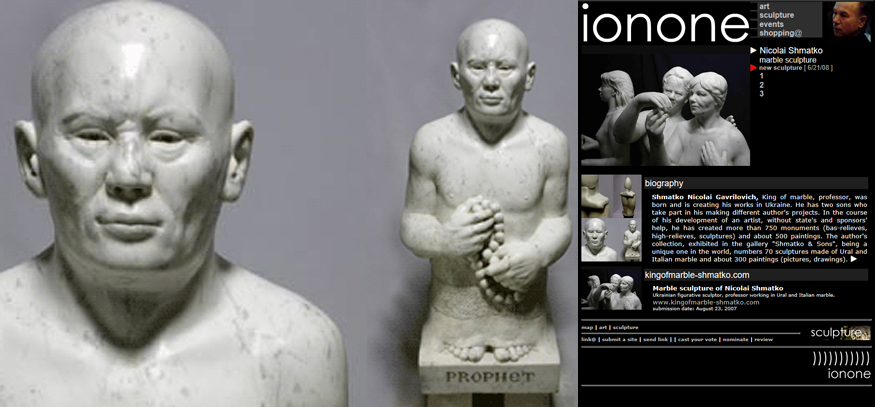

Shmatko Nicolai Gavrilovich, King of marble, professor, was born and is creating his works in Ukraine. He has two sons who take part in his making different author's projects. In the course of his development of an artist, without state's and sponsors' help, he has created more than 750 monuments (bas-relieves, high-relieves, sculptures) and about 500 paintings. The author's collection, exhibited in the gallery "Shmatko & Sons", being a unique one in the world, numbers 70 sculptures made of Ural and Italian marble and about 300 paintings (pictures, drawings).

read more »

Ruben Talberg (*1964 born in Heidelberg) Israeli-German painter, sculptor, photographer. He initially lived in Frankfurt, then in America and Israel. His first solo-exhibit was presented 1986 in Heidelberg. Talberg’s art constitutes an act of liberation. His family is related to Irving G. Thalberg, founder of the Memorial Award, Los Angeles. Talberg ranks among the most successful Israeli-German contemporary artists. He is reputed to represent Young Jewish Art (YJA). In his oeuvre he deals with antagonistic positions like Nature & Alchemy, Asymmetry & Dynamics or Eros & Thanathos. He works in various media such as: Painting, Sculpture, Photography, Video, Installation, Lyrics. During the last decade he intensified his interest for Jewish mysticism and magic. On extensive travels as recently to the USA and Spain he created new serials of photography that in turn generate the base for new painting cycles. Likewise the surfaces of his paintings teem with references to Aramaic letters, Voodoo or Egyptian symbols, Chinese economic numbers. Talberg is a member of the German Association of Fine Artists (BBK), VG Bild-Kunst, ROTARY International, New York Artists Equity Association, Inc. (NYAEA). Talberg lives and works in Offenbach and Miami. read more »

www.rubentalberg.com

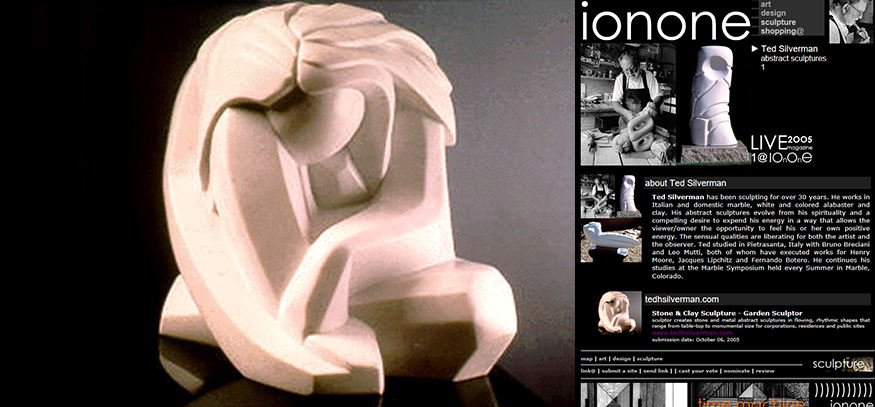

Ted Silverman has been sculpting for over 30 years. He works in Italian and domestic marble, white and colored alabaster and clay. His abstract sculptures evolve from his spirituality and a compelling desire to expend his energy in a way that allows the viewer/owner the opportunity to feel his or her own positive energy. The sensual qualities are liberating for both the artist and the observer. Ted studied in Pietrasanta, Italy with Bruno Breciani and Leo Mutti, both of whom have executed works for Henry Moore, Jacques Lipchitz and Fernando Botero. He continues his studies at the Marble Symposium held every Summer in Marble, Colorado.

www.tedhsilverman.com

September 11 is a day that will never be forgotten, as well as its consequences - war. The german artist Helga Kreuzritter´s paintings with the title "2001" ("2001 - The Attack", "2001 - Victory?"; "2001 - Peace?")are her contributions as reminders of this atrocious attack, but they also ask questions: Was the "victory" really a victory? And what about what was called "peace" at the end of the war? Helga Kreuzritter did create these paintings soon after the end of the Afghanistan war. In the meantime, the course of the political developments justifies her scepticism. These paintings are impressive examples for the language of an artist. A network of barbed wire symbolizes the powers of evil ("2001 - The Attack"); a banner at the top of a hill is a signal for victory ("2001 - Victory?"); a crucifix and veiled warriors are representations for the conflict between religions ("2001 - Peace"). These paintings, together with other paintings, sculptures and objects by Helga Kreuzritter, will be on display during an art exhibition in Vienna/Austria, at the well-known art gallery KANDINSKY, from June 6 until June 18, 2005 read more »

www.helga-kreuzritter.com

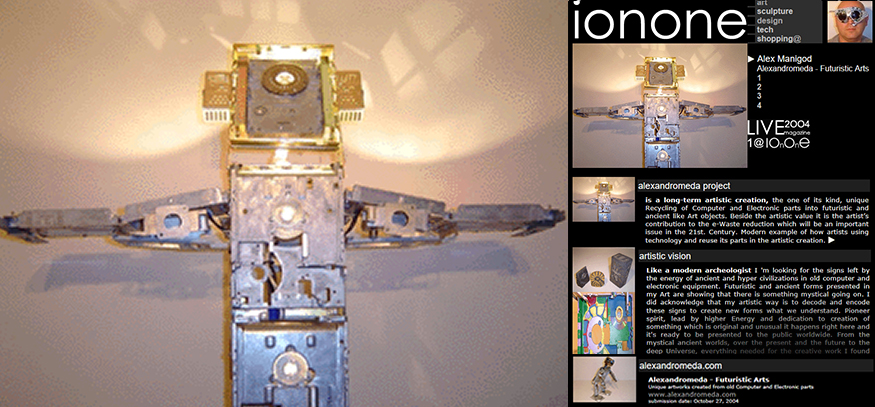

Alexandromeda project is a long-term artistic creation, the one of its kind, unique Recycling of Computer and Electronic parts into futuristic and ancient like Art objects. Beside the artistic value it is the artist’s contribution to the e-Waste reduction which will be an important issue in the 21st. Century. Modern example of how artists using technology and reuse its parts in the artistic creation. Like a modern archeologist I 'm looking for the signs left by the energy of ancient and hyper civilizations in old computer and electronic equipment. Futuristic and ancient forms presented in my Art are showing that there is something mystical going on. I did acknowledge that my artistic way is to decode and encode these signs to create new forms what we understand. Pioneer spirit, lead by higher Energy and dedication to creation of something which is original and unusual it happens right here and it's ready to be presented to the public worldwide. From the mystical ancient worlds, over the present and the future to the deep Universe, everything needed for the creative work I found through transformation of the old electronic and computer parts to the new form of existence. Future Vision arts example and High Tech Art for the 21st. Century

www.alexandromeda.com

Apparently, Nicholas Serota, director of the Tate Modern, was not prepared to let the name of Donald Judd (1928-1994) silently fade from our memories - did he not do his utmost to make the man famous in the first place? Ten years after his death - sixteen years after the last substantial exhibition - he presents a big retrospective of the work of the artist who has 'changed the course of modern sculpture''. The exhibition travels to Düsseldorf (19/06 to 05/09/04) and Basel (02/10 to 09/01/05). Heavy artillery, that makes us ask what has to be canonised here at all cost. Who is this master and what everlasting works did he leave to posterity?

BOXES

'Il faut être un homme vivant et un artiste posthume' Jean Cocteau, Le rappel à l’ordre.

From 1947 to 1953 - in the heydays of the very 'abstract expressionism' that soon will be promoted as the panacea of the Free World with a little help from the CIA* - Donald Judd studied at Art Students League in New York, the College of William and Mary and the Columbia University. Meanwhile, he is already fully active as an art critic and a painter. Already in 1957, he has his first show in the Panoramas Gallery - although from the paintings exhibited there no trace is to be found in what is announced as the 'first full retrospective'. But things are not going well with the Action Painting in New York. Andy Warhol comes to replace Jackson Pollock. Accordingly, the expressionistic gestures on Judd's canvasses are replaced with a baking tin (1961).

read more »

Born in 1965 in Warsaw. Studied at the Faculty of Interior Architecture in Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. In 1990 has made a diploma with distinction (work: MY PRIVATE CHAIRS). Participated in several exhibitions in Poland and abroad (solo exhibitions: HOME/1993, OBJECTS/1995, SHOWING IN A FACTORY/1997, MEBLARIUM 1/2002, OPERA GALLERY/2003). Created a lot of furniture-objects, sculptures, internal arrangements.

www.grunert.art.pl

From Skagen painters to Damien Hirst

On 26 January 2008 the new ARKEN is opening. The premiere exhibitions offer new light on the Skagen painters, a solo show with the bright young thing Andreas Golder and not least: A new hanging of ARKEN’s Collection, now for the first time exhibited permanently and including a unique Damien Hirst room.

At last! After 2½ years of construction ARKEN can open wide its doors to the new extension. 5,000 m2 of exhibition space will be the end result – twice as much as now, making ARKEN one of Denmark’s biggest museums. The new ARKEN will continue the course of shedding new light on the classic modern art. At the same time the focus on contemporary art will be intensified through both special exhibitions and a permanent exhibition of the museum’s collection.

read more »

'An analysis of Yeat's 'Leda and the swan' against the background of his work and the history of art'

Whatever your stance on Yeats’ poetry, you would not deny that the man has written a poem the charms of which no devotee of art can possibly resist: the unparalleled ‘Leda and the swan’ which sounds as follows

LEDA AND THE SWAN

A sudden blow: the great wings beating still

Above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed

By the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill,

He holds her helpless breast upon his breast.

How can those terrified fingers push

The feathered glory from her loosening thighs?

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?

A shudder in the loins engenders there

The broken wall, the burning roof and tower

And Agamemnon dead.

Being so caught up,

So mastered by the brute blood of the air

Did she put on his knowledge with his power

Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?

THE TECHNICAL BEAUTY

of this poem just catches the eye.

To begin with, there is the structuring of the whole episode. The poem may be divided in two halves. The first comprises the violent encounter of Zeus and Leda ending in ‘a shudder in the loins’, whereas in the second both spatial and temporal perspectives widen into infinity.

This partition matches the division of the sonnet into octave and sestet. Which is marked through the similarity of the two bold phrasings summarising the event in its constituent elements: ‘A sudden blow’ initiates the octave and ‘a shudder in the loins’ the sestet. It also coincides with a shift in the temporal perspective. The octave is in the present tense; the first half of the sestet at once projects us in the far future ‘(Agamemnon dead’); from this vantage point we look back on the violent encounter (‘did she put on his knowledge…?’) that now is irrevocably referred to the past. And this binary structure is echoed in the grammatical construction: each half comprises two sentences, each encompassing a single strophe, the first and the third of which are affirmative, the second and fourth interrogative. The alternation of affirmation and interrogation goes hand in hand with a change in the commitment of the reader, who seems to identify himself with the swan in the affirmative sentences, whereas in the interrogative ones he seems to ask himself how Leda might experience her brutal overpowering.

Over this apparent articulation in two halves is superposed a second, this time asymmetric, binary structure. It is marked by the typography: ‘being caught up’ is referred to the second half of the sestet. In the first half of this partition the unstoppable unfolding of the proceedings is depicted into its furthest consequences: everything is rendered in the present tense. In the second shorter half, written in the past tense, the deeper meaning of the event is fathomed.

A further counterpoint to the central partition is the shift in spatial perspective. No swan is staged, but ‘great wings’, ‘dark webs’, ‘his bill’ ‘his breast’, ‘the strange heart’ ‘the brute blood of the air’ ‘the indifferent beak’. And also from Leda we only catch a glimpse of ‘her thighs’, ‘her nape’, ‘her helpless breast’, ‘those terrified fingers’, ‘ her loosening thighs’ and ‘the strange heart’. In short: a perspective familiar to all those who happen to be cast by the spell of the flesh. Only with ‘body’, but foremost with ‘the feathered glory’ and its the counterpart: the ‘staggering girl’, does the camera seem to zoom out. But it is only when we are faced with the consequences of such promiscuous entangling of body parts that we are allowed a panoramic view on the whole: ‘The broken wall, the burning roof and tower and Agamemnon dead’. Thus, the temporal partition in present and past tense is joined by a spatial partition between the more involved close up and a rather contemplative panoramic view.

As far as meter is concerned, it is apparent that the diction only unwillingly complies with the train of the iambic pentameter. We have to first witness the forceful resistance of the ‘great wings beating still’, the ‘dark webs’ and her ‘nape caught’ – an accumulation of stressed syllables wonderfully echoing the ‘sudden blow’ of the swan’s wings. But even when the metrical order seems to be restored, the asymmetry of the grammatical structure continues to oppose the regular flow on a more abstract level. Most conspicuously in that masterly - unforgettable - first half of the sestet:

A shudder in the loins engenders there The broken wall, the burning roof and tower And Agamemnon dead.

The rhythm determined by the alternation of adjective and noun as it is initiated in ‘broken wall’ and ‘burning roof’, is not carried on in ‘tower’, which has to manage without adjective. But the latter surfaces again in the consequent ‘Agamemnon dead’, albeit this time after the noun. Over the repetition in the word rhythm a second pattern determined by the alternation of adjective and noun is superposed: a rotation from initial position to end position. To the unparalleled rhetorical effect that the whole procedure of begetting life is turned into its very opposite. To which we shall return below.

Next to the word rhythm and the alternation of adjective and noun also the sonorous body of language is summoned up to evoke the encounter. Think only of the way in which ‘he holds her helpless breast’ unabashedly renders Zeus’ heaving. Not to mention the ‘broken wall, the burning roof and tower and Agamemnon dead’, the infernal sonority of which only joins the solemn stride of the meter to a veritable funeral march reminding of Wagner’s ‘Siegfrieds Tod’.

The theme

But let us first introduce the theme. The story of Leda stems from Greek mythology. Leda is the Spartan king Tyndareus’ wife. When she saw her chances, she did not hesitate to exchange her royal husband for a god: Zeus, even when he approached her in the shape of a swan. Which yielded her four eggs. Out of which not only hatched Castor and Polydeukes as well as Clytemnestra, but first and foremost the Helen of the Trojan war.

Of old, the theme has been very popular in the plastic arts. It will turn out to be very fruitful to first examine how it has been handled there.

The representation of loving couples has always been a problem in the plastic arts. For the obvious reason that of a couple intertwining – Brancusi’s animal with the two backs – the most enticing fronts are hidden from view. Literature knows not such problem. When reading Ovid’s verse ‘ Leda is lying between the swan’s wings’ (Metamorphoses VI, 109), not only do we see before our mind’s eye the pair of wings embracing Leda, but the body covered by these wings as well, not to mention the experience of the most diverse bodily sensations. In painting or sculpture, on the other hand, we are not faced with malleable representations for diverse senses, but with a concrete visual image. The painter that from the encounter of Leda and the swan would only show us the sight of spread out wings would not show at all: he rather would hide from view precisely what we so dearly wanted to see.

The classical solution consists in staging the bodies immediately before their entwining. But such is not a becoming solution in the case of Leda and the swan: we precisely wanted to witness the proceedings after the encounter! And to make a picture thereof raises a lot of problems.

To begin with, there is the tension between the impressive figure of Zeus and the rather humble shape of the swan wherein he is transformed. Especially since the little bird also has to mount the huge female body. Before the mind’s eye we inconspicuously adapt the shape of the swan, as with the already cited verses of Ovid. But when the scene is graphically depicted there before our very eyes, the discrepancy between the mighty Zeus and the rather humble shape of the swan catches the eye. It must be granted, though, that the very same humble shape also yields an unexpected gain: the beast with two backs has on one side exchanged a broad back with a slender neck, to the effect that nothing any longer prevents the full exposure of Leda’s enticing front (see Corregio’s Leda, 1530, Berlin Dahlem).

But whoever might reconcile himself therefore with the humble elongated shape of the swan, cannot possibly let it pass for the mighty Zeus. Unless he focusses on Zeus' mighty member: only of this true Adam can the swan be the becoming metamorphosis – the long neck then stays for the stem of the penis, the head for its glans, the winged trunk for the scrotum. And such life-sized organ cannot fail to head straightforward towards its goal: also in the real world the stretched out neck of a swan reaches to the genitals of a woman standing. Although the beak of a real swan, as opposed to that of reckless goose, happens to rather modestly bend downwards.

La figura serpentina

Of course, the painter might proceed to adapt the shape of the swan to Leda’s body. But he then faces new problems. To begin with, also the wings grow accordingly - and they come to stand higher at that. Would we let them play the role of the lover’s arms embracing his beloved, her beauty were hidden from view by a pair of wings again. Far more interesting, then, to let them flap and express the superior strength of the swan. The task of subduing Leda’s body is then relegated to the beak which has to catch Leda in her nape. This solution has been chosen in the Hellenistic relief above. The swan’s body, running out in the slender neck, no longer embodies the erect member, but the entire body of Zeus. To the effect that the penis is relegated to the lower regions where it is reduced to its former proportions. But there again it comes to face still other problems. Although of all the winged beings the swan has perhaps the biggest penis – rather: something that can be called a penis – it does not end up in a vagina, but in an arse – and that was not precisely what Zeus was after. In the Hellenistic relief the dorsal approach implied by the catching in the nape is replaced with a frontal one, as is more becoming to men – let alone gods! But the swan seems not to be able to cope with the frontal approach: Leda has to adjust something or other with her hand! The frontal twist in the lower regions finds its counterpart in a dorsal twist in the higher spheres, were the slender neck graciously bends downwards to catch Leda’s nape from the back. To the effect that the swans’ webs are no longer stamping on a feathered swan’s back, but on Leda’s white thighs. Also on the Roman representation below, where the artist has equally chosen for blowing up the swan, the focus is on the proceedings in the genital zone. And also here things seem not to work properly: Leda has to pull the swan's legs to get things straight. So, only after some considerable twisting, turning and adjusting can they find each other, Zeus and Leda.

In the ancient representations, the focus is on the problematic nature of the encounter of beast and man. We have to await the heathen Renaissance to witness a deepening of the approach and the corollary invention of more convincing solutions.

Da Vinci's Leda

It is da Vinci (1452-1519) who sets the tone for the new approach. In his first drafts of the theme he tries to solve the problem of the shape by letting Leda bend, as parents do when trying to adapt to the small stature of their children – or Mary when kneeling before her holy son. But on the eventual painting (only known through its copies), Leda is standing again, and she is approached by the rather impressive swan on her side.

The interesting thing is that, in both versions, the beak no longer reaches to the navel, but to Leda’s very lips. It is no longer out at penetrating the vagina, let alone to catch Leda in her nape: its declared aim is bluntly Leda’s mouth. One of the formerly flapping wings now gently embraces Leda’s hip. And such entwining does hide nothing from view. On the contrary: since the encounter has shifted upwards, Leda can be taken under the arm from behind, to the effect that her magnificent front remains visible in all its splendour. It appears that the oral approach meets some resistance: although Leda willingly coils herself in the swan’s wings and turns her breasts toward the swan, she teasingly withdraws the lips in her face. And the same goes for the hesitating hips and her hanging leg.

Michelangelo's Leda

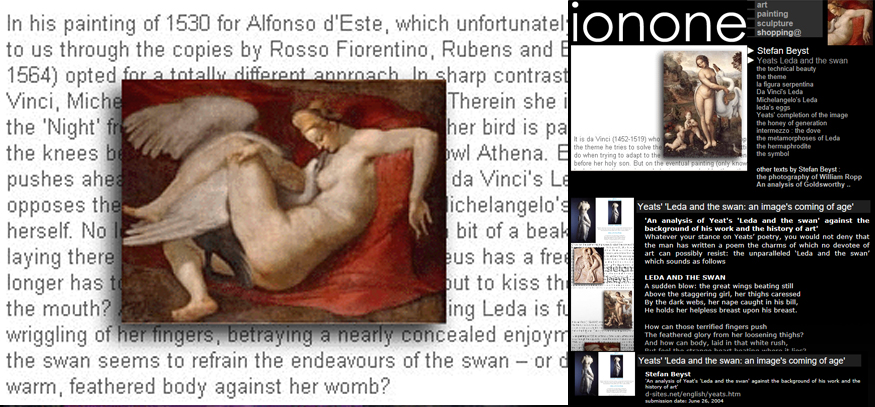

In his painting of 1530 for Alfonso d’Este, which unfortunately enough has only come to us through the copies by Rosso Fiorentino, Rubens and Bos, Michelangelo (1475-1564) opted for a totally different approach. In sharp contrast with the Ancients and da Vinci, Michelangelo has his Leda lying supine. Therein she is a further development of the ‘Night’ from the Medici chapel – where another bird is paying his respects under the knees before the entrance of the gate: the owl Athena. But Michelangelo equally pushes ahead with da Vinci's innovation. While da Vinci’s Leda rather modestly opposes the indecent proposals of the swan, Michelangelo’s willingly abandons herself. No loonger needs she to be forced by a bit of a beak in her nape: she is laying there for the kissing. To the effect that Zeus has a free neck: his beak no longer has to catch Leda in her nape, his is about to kiss the lips – or to penetrate the mouth? And the complicity of the half-sleeping Leda is further emphasized by the wriggling of her fingers, betraying a nearly concealed enjoyment. Only the right arm of the swan seems to refrain the endeavours of the swan – or does it rather press the warm, feathered body against her womb?

And that reminds us of the fact that Michelangelo’s swan is granted its natural proportions again. Which induces it not only to penetrate the mouth with its beak, but also the vagina with its penis: it suffices to get a glimpse on the position of the tail, which is spread like a fan over the vagina and the black web bluntly plopped down on the soft inner side of Leda’s white thighs. Although the dark tone of the tail may be motivated through its position in a shadow zone, it first of all seems to be the emanation of what it conceals: the black penis of the swan – vicariously made visible in that equally black web. Also another colour has shifted to the periphery: the red of the equally concealed vagina. The red draperies whereon Leda is spread are the nearly concealed representation of a vagina (see also the print of Bos). Not only Michelangelo is fond of making rather obscene representations shimmer through seemingly neutral draperies...

Thus, da Vinci’s swan as well as Michelangelo’s is resolutely turning perverse. But both masters immediately keep it on the straight and narrow. With this conflict corresponds the ambivalent filling in of the body of the swan. Although da Vinci’s swan takes the shape of a full-fledged human body, Leda only has to disappointedly turn away from a void, while at the same time the swan’s greedy beak is deliberately out at her lips. And even when Michelangelo’s swan remains a small bird, not only does its agitated body stubbornly try to penetrate the vagina, even more eagerly does the greedy neck edge its way between the breasts toward the mouth.

Leda's eggs

The perverse move away from the genitalia to the neck and the beak finds its counterpart in the equally perverse move away from fertilisation and birth. No longer do penises or vaginas come to spoil the fun of begetting. And with birds also birth is no longer a question of repugnant slime, but a clean affair of white shells: the immaculate conception of the white egg (see: ‘La Cane et son omelette', forthcoming’).

And that holds especially for our story. The four children springing from the encounter of Zeus with Leda were not precisely born, they rather hatched out of eggs. Already in his drafts does da Vinci throw Leda her offspring in the face. With Michelangelo, where the swan is nevertheless rather busy down there, no eggs are to be seen, at least on the copies of Rosso Fiorentino and Rubens. On the print of Bos already one egg has hatched and another one on the foreground is on the verge of doing so.

Even when the emphasis on the consequences of the deed is in line with the genital-fertile defence against the perverse proceedings of the swan’s neck, the fact that birds have to do without a penis and a vagina perverts their reproductive efforts from within.

And that equally holds of Yeats. Even when no eggs are mentioned in his sonnet, in ‘Among school children’ the poet stages a ‘Ledaean body’ wherewith he feels united as ‘the yolk and white of the one shell’. And that reminds us that we are dealing here with Yeats’ Leda. But only now are we ready to tackle the sonnet properly.

Yeats' completion of the image

According to Charles Madge* the above mentioned Hellenistic relief would have inspired Yeats. Which is evidenced by the flapping of the wings, the emphasis on the web on Leda’s thighs, but foremost by the way in which the swan catches Leda’s neck and presses her face against its breast.

But equally right are all those who traditionally maintain that the poem is inspired by Michelangelo’s Leda. To begin with, Yeats’ Leda does not stand upright, as she does on the Hellenistic relief. She is lying supine, as with Michelangelo. And even when the webs on Leda’s thighs may also appear on the relief, marble has no colour, and it is precisely the resonance of that colour black that is more than echoed in that splendid ’her thighs caressed by the dark webs’. But foremost those ‘terrified fingers’ betray that also the painting of Michelangelo lies at the roots of Yeats’ sonnet. Even when they ward off, rather than wriggle out of pleasure. The mere fact that Yeats’ Leda uses frail fingers rather than full arms to ward off the brutal swan, at once reminds us of the fact that also on the Hellenistic relief Leda does not ward off. With her full arm she rather eagerly extends a helping hand – her wriggling fingers being hidden from view through the thighs.

It is apparent, then, that Yeats must have been strongly impressed with the greediness of Michelangelo’s swan and the complicity of his Leda, but foremost with the eagerness wherewith the Hellenistic Leda helps the swan reach its goal. Which does not prevent that this erotic fervour equally unleashed a strong counter-current in Yeats. Which departs not so much from the proceedings under Michelangelo’s fanning out of the tail, as rather from the more convincing proceedings between Leda’s thighs on the Hellenistic relief. Through such regression from the ‘Renaissance’ to ‘Antiquity’, the pushy beak that effortlessly reaches its goal, is whistled back to the place where it belongs: between the thighs. And to seal the genital metamorphosis Yeats also borrows the most striking gesture of the Hellenistic relief: the compelling force wherewith the swan catches Leda in the nape, which neutralises the organ of lust into a mere instrument. And the crowning glory of this work are those ‘terrified fingers’, wherein Yeats utterly negates the seemingly denied complicity of da Vinci’s Leda and the nearly concealed complicity of Michelangelo’s Leda.

It seems as though Yeats reduces the ambivalence between perverse and fertile strivings to the sole genital proceedings. The scale seems to resolutely tip in the direction of the pole of negation. In line with this negation Yeats stresses the reproductive consequences of Leda’s encounter: the ‘shudder in the loins’ ‘engenders’ – an echo of da Vinci’s emphasis on Leda’s eggs.

The honey of generation

But that very ‘engenders there’ following the ‘shudder in the loins’ puts a heavy damper on the triumph of the member foolhardy. What is begotten there is not precisely suited to welcome the deed of procreation: whoever would like to be the father of ‘the broken wall, the burning roof and tower and Agamemnon dead’? Which of course is a reference to the Trojan war waged on occasion of the unfaithfulness of Helen, one of Leda’s chicks. The fratricide is represented through another pair of chicks: Castor and Polydeukes. Also on da Vinci’s painting the hardly hatched mortals are already attacking each other. And the role of the fourth chick is played by Agamemnon, who was murdered by Helen’s (twin) sister Clytemnestra (in Aeschyles’ version).

In that ‘Agamemnon dead’ resounds still another reproach to the deed of begetting. In ‘Among schoolchildren’ Yeats complains the ‘youthful mother’ ‘honey of generation had betrayed’:

What youthful mother, a shape upon her lap (...)

that must sleep, shriek, struggle to escape (...)

Would think her son, did she but see that shape

With sixty or more winters on its head,

A compensation for the pang of his birth

Or the uncertainty of his setting forth?

What the honey-sweet ‘shudder in the loins’ engenders, is not so much life, rather death. Not to mention all those minor burdens that the poor mortals lift on their shoulders for the lust of one moment’s sake. In the short term the ’pang of birth’. In the somewhat longer term: the care for their progeny ‘that must sleep, shriek, struggle to escape (…)’. And at long last the growing realisation that all these offers have been in vain: we only beget to doom to death. For the sole taste of honey’s sake!

No wonder that love recoils in the face of such dreadful perspective! Yeats, though, never speaks out this truth. He rather prefers to state without any further explanation that love is merely an transient transport – or to phrase it with Schopenhauer: a cunning of nature that is merely out at eternal reproduction. Time and again Yeats stresses the transience of love. In ‘Never give all the heart’ he holds that:

it fades from kiss to kiss;

for everything that’s lovely is,

but a brief, dreamy, kind delight

That is precisely why he warns us ‘Never give all the heart’. With as an encore:

‘He that made this knows all the cost,

for he gave all his heart and lost’

Which of course causes the soul to leave her limbs, as in ‘The lady’s second song’:

Soul must learn a love that is

Proper to my breast,

Limbs a love in common

With every noble beast.

Which again sheds a new light to the swan as ‘the noble beast’

Intermezzo : the dove

Also in ‘the Mother of God’ a woman is impregnated by a bird, equally ‘wings beating about the room’. Although this time it is a dove, and although this time not a daughter is hatched, but a son. Destined to death by his very father…

What is this flesh I purchased with my pains,

This fallen star my milk sustains,

This love that makes my heart’s blood stop

Or strikes a sudden chill into my bones

And bids my hair stand up?

Herein Yeats joins a tradition that we swept under the carpet to allow ourselves a rapid transition from Antiquity to the Renaissance. But just as only as a metamorphosis of Mary Venus is reborn on Botticelli’s painting, just so the genuflection of da Vinci’s Leda before her eggs is a nearly concealed echo of Mary falling on her knees before her son Jesus. Who was brought to the world to redeem us of the sins of precisely the fratricidal twins that hatched from the swan’s eggs…

The metamorphoses of Leda

Indulging in the kind of love he has in common with ‘every noble beast’ leads to man’s fall. The endeavour to break the fall unleashes the perverse move. The tempestuousness wherewith the unruly procreative violence, embodied in the flapping of the wings of dove and swan alike, is enforcing itself, unleashes an even stronger unwillingness to surrender. For only at first sight does Yeats negate Renaissance’s perverse strivings. In fact Yeats faces us with the central conflict that sets alight the perverse fire, while at the same time allowing the perverse counter-move to expand in ever wider circles.

To begin with, Leda is overpowered by a ‘noble beast’ and not by a mere man or god. The metamorphosis of man into bird releases the male of precisely the source of all evil. And even when Yeats neutralised Michelangelo’s greedy swan neck to a compelling beak, the perversion literally returns through the back door: the catch in the nape implies an approach from behind. In ‘Crazy Jane talks with the Bishop’ (Words for Music Perhaps, VI) Yeats himself betrays what is performed there in the lower regions as the counterpart of the ‘nape caught in his bill’ and under the guise of a ‘shudder in the loins’:

Love has pitched his mansion in

The place of excrement.

The obliteration of the penis is completed by the vagina’s metamorphosis into a cloaca.

But the repressed returns not only through anal channels. The process of desexualising strides further along a path that also here has been paved by painters. Michelangelo’s Leda is completely naked. The impression of nakedness is only enhanced in that Leda’s hair is covered with a skin-coloured headgear. And neither is there left any trace of the pubic hair: it is covered by the fan of the swan’s tail. Which only enhances the contrast between the white-feathered body of the swan and the utterly naked body of Leda. But the very sharpening of the contrast unravels a secret affinity. Precisely because Michelangelo smoothes away the difference between naked skin and hair, it all the more comes to catch the eye that Leda’s body ends up in a horny headgear – a nearly concealed echo of the way in which the feathered swan’s body changes in the horn of the beak. Such surreptitious assimilation of the ‘Ledaean body’ is further enhanced through Michelangelo’s emphasis on those wriggling fingers and those remarkably agile limbs. Also da Vinci’s Leda seems eager to become a swan: he lets her whole body – la figura serpentina – balance in opposite directions alongside diverse axes. An echo of the above described convolutions that had to be performed to make Leda’s and the swan’s body match?

But the metamorphosis of Leda in a swan does not halt with the smoothing out of her hair and the voluptuous posture of her body: Leda also lays eggs. That seems to go for itself. But on a closer look we would rather expect eggs when a human male impregnates a female bird. When, conversely, a bird impregnates a woman, it would be more obvious that she would cuddle little swans in her womb, until at last little swan beaks would protrude from the vagina rather than children’s heads – in a variant of the story it is Nemesis that lays the scorned eggs… after her previous transformation in a goose. Not only in her alluring demeanour and her voluptuous gestures has Leda become a swan, her metamorphosis comprises her organs as well: she lays eggs and has become a bird. The metamorphosis from vagina to cloaca was only a prelude to the metamorphosis from mammal to winged bird, the sequel to Zeus’ becoming a swan.

The hermaphrodite

Also Yeats seems to be ridden by the desire to smooth away every difference between the swan and Leda. The metamorphosis of the loving couple into a couple of birds is an old dream of Yeats’. Does he not sing in 'The white birds':

‘For I would we were changed to white birds on the wandering foam: I and you!’

With Yeats, the smoothing away of the difference between man and animal seems to encompass the smoothing away of the difference between man and woman. An obvious solution is their metamorphosis into a swan. It is rather impossible to tell a male swan from a female: both share a virginal front. And that sheds a new light on the fact that it is Zeus that presses Leda’s breast against his: ‘he holds her helpless breast upon his breast’. On the Hellenistic relief Zeus does not press Leda’s breast against his breast but Leda’s face. And this is also the case in a former version of the first quatrain:

A rush, a sudden wheel, and hovering still

The bird descends, and her frail thighs are pressed

By the webbed toes, and that all-powerful bill

Has laid her helpless FACE upon his breast.

Leda’s face upon Zeus’ breast: this immediately reminds us of a mother breast-feeding her child. But it is not Leda who breast-feeds Zeus as on Bacchiaca's painting above. It seems as if through his metamorphosis into a swan Zeus is at the same time turned into a mother. As if the desire of the mouth, that the beak had to give up to catch Leda in the nape for copulation’s sake, surfaces again in the shape of the nipples growing out of the breast of the swan – which, otherwise than with mammals, shows no sexual difference between male and female.

But Yeats must have been equally disturbed by the difference between mother and child as by the difference between man and woman. That is why in the second version is restored the reciprocity that previously existed between beak and lips: Zeus no longer presses Leda’s head against his breast, but her breast against his. To be more precise: his breast without breasts against Leda’s breast with two breasts. And to also smooth away this last asymmetry, they both feel the same in that region: if not each others bosom, than at least each other heart beating!

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?

Which immediately reminds us of the already quoted verses from ‘The lady’s second song’:

‘Soul must learn a love that is

proper to my breast,

limbs a love in common

with every noble beast’

Whereas on the level of the limbs protrusion and hole oppose each other, on the level of the soul two hearts feel each other beating. From beast to breast, the journey goes through three stations: from sperm, through milk, to blood. From the feeding breast to the beating - pumping - heart: such shift is indicated in the already cited verses from ‘The mother of God’ where Mary complains about her godly son:

This fallen star my milk sustains,

This love that makes my heart’s blood stop

A similar shift is at work in Luca della Robbia’s Leda, where the swan is not out at Leda’s breast, but rather at the place beneath it where Christ shows his wound:

And that is how Leda turns into something of a Jesus Christ. Who in his turn is often represented as a pelican feeding his young with the blood flooding from his heart – the very reversal of the image of Mary with the divine child on her breast. It seems as if we are landed up in a veritable whirl of the sexes and the generations.

But there is more. The first version sheds a new light on some oddities in the second version, that otherwise might have inadvertently escaped our attention. With the image of a swan descending from heavens in mind, we are ready to read the ‘in’ in ‘laid in that white rush’ as a ‘by’. But that very same ‘in’ cannot fail to suggest that it is not the swan, but Leda who descends from heavens ‘in that white rush’. And that lends only its full weight to the wording in the second quatrain of the first version where Leda is bluntly laid ‘on’ that white rush:

How can those terrified vague fingers push

The feathered glory from her loosening thighs!

All the stretched body's laid on the white rush

And feels the strange heart beating where it lies.

In line with such increasing osmosis of the sexes lies a second shift. In the first version ‘body’ refers to Leda’s face pressed on Zeus’ breast . But in the second version ‘body’ refers to the embracing bodies as such - Leda’s body as well as the body of her swan:

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?

The incipient metamorphosis of Leda turns out to be the mere prelude to a further metamorphosis: Zeus’ transformation in a woman/mother and Leda’s concomitant transformation in a man. Or to be more precise: both come to partake of the hermaphrodite by incorporating each other. And hence can eternally entwine, like Aristofanes spherical beings, hinted at in the verses:

‘For nothing can be sole or whole

that has not been rent’

which – significantly enough – immediately follow the already cited ‘Love’s mansion in the place of excrement’ (Crazy Jane and the Bishop). Also in ‘Among School Children’ the reunification in the egg is described: ‘

and it seemed that our two natures blent,

into a sphere from youthful sympathy,

Or else, to alter Plato’s parable,

Into the yolk and white of the one shell

The hermaphrodite is only a figure of the denegation of multiplicity as such. Its completion is the self-sufficient solitary – the one and only God – hinted at in ‘A prayer for my daughter” where ‘the soul’ learns at last

that it is self-delighting,

Self-appeasing, self-affrighting,

and that its own sweet will is Heaven’s will;

The symbol

And so we have laid bare all the roots and ramifications of Yeats’ magnificent image. It appears that Yeats has with unparalleled mastery condensed the central conflict of human existence, far more concisely - since brought to a head - than da Vinci and Michelangelo.

With this reading in mind, many an accepted interpretation rather evaporates. Foremost Yeats’ own interpretation. He believed that the age of democracy was going to its end and that a government ‘from above’ would be installed to subdue the anarchic masses, as in Russia. But Yeats himself betrays how, when working on his Leda, he was so caught by the image of the bird and the girl, that ‘all politics went out of it’ (Cullingford). And we readily believe him. Did he not write himself (in ‘Politics’):

How can I, that girl standing there,

My attention fix

On Roman or on Russian

Or on Spanish politics?