art | architecture | design | digital | gallery | illustration | music | painting | photography | sculpture | video

In this biography I will concentrate upon why I became an artist and my personal background for becoming nothing else. I was born in 1949 in the Danish city Brande, which since then has become famous for its murals of which - of course - the most popular is that of mine. My father was a very busy man avoiding any domestic conflicts by telling a joke, leave home and work, work, work. My mother was psychologically extremely unbalanced - for reasons I understand today. I was supposed to have been a girl. But I surely was a boy. I had to do everything on my own. I never have really talked to anybody until recently. I became a loner. The only baggage from my childhood was to accomplice something in order to have any attention. And to avoid feelings by joking and working. I became a loner and a fighter. Fighting for mental survival. I had all the "success" that anybody could want. I was a very bright student in school. I was a very talented soccer player. I was a very talented yachtsman. I had the most beautiful girlfriend with a rich family. I graduated from high school and I had a little attention, but just a little. I was married to the beautiful rich girlfriend and got a little attention, but just a little. I had three wonderful sons and got a little attention, but just a little. I was educated in computer science - graduating with "a straight A" and I got a little attention, but just a little. I became the boss of a municipality's computer department and I got a little attention, but just a little. I started my own businesses in the computer world. I became a managing director and later chairman of the board of my own companies. I suddenly got some attention. It was devastating. I sold the companies becoming one of the first computer millionaires in Denmark. I became an artist. A successful artist. Being a millionaire and a successful artist I had my family's full attention. That was what it took. As I realized this I took a break to recover from that lifelong depression due to a totally lack of reasonable values. As I had accompliced to reach the goals I was taught - and reviled the emptiness of those goals - sure a break was necessary. In this period of time I made the paintings in "Sad Days" - Exhibition of Paintings. They are existential, very emotional expressionistic paintings. I went back to a new life. I became a person. I became me. Figuring out my own goals. I re-found my own very unique artistically expression - for the right reasons - in simple shapes and bright colors. Which is not only an artistically expression - it's an attitude of life.

My artist statement is: Colorful zen-simplicity in art as in my life.

read more »

Since the end of 2002, I´ve dealt intensively in creatively

combining digital photography with different rendering and image-processing programs. With the motto „everything is possible! – possibly is everything nothing?“ I feel my way ahead, image for image. My own photos, foreign material – exchanged through the web, altered or left unchanged, partially or completely taken over... To give fantasy free rein, to unabashedly refuse to reject unusual material to the cyber-bin, the possibility to continuously change and yet adhere to the original idea – all this has led me into a new wide-open territory. Wide-open territory with unforseen creative possibilities. Wide-open territory restricted only by one´s own fantasy. Wide-open territory where for me now, no limits are in sight ...

Georg Hübner, born 1962 in Vienna. In 1993, after many years in music, I turned to photography. Impressed by the expressiveness of high-quality fine art prints, I devoted my initial years to the fundamentals of photography and my interest for positive and negative techniques, as explained in the literature from Ansel Adams. Several years later, after excursions into various segments such as infrared, landscape and spontaneous snapshot photography, I developed my own style, influenced by Czech photographers Michal Macku and Jan Saudek. In November 2002 I began combining "classical" analogue and digital photography. Many of the expressive possibilities, before only obtained through incredible efforts in the dark room, were now at hand, and yet more precise and time-saving than previously. Pictures occupy my thoughts long before they are transposed. Experiences, feelings, dreams.... these are the material from which the real forms arise. With the aid of files of my own and others, as well as 2D and 3D - program, the final picture is created. The challenge for my finished images is to project and represent those fleeting moments of joy and fear, of high and low spirits, of fun and madness ...

www.pixart.at.tf

Horkay's Museum Factory series combines original drawn and painted images, appropriated masterpieces, photographs, artists' signatures and commercial logos. These elements are digitally assembled, i.e., collaged, to create a single, layered moment reflecting different places and times. This work is post pop, i.e., post modern pop art. Whereas Warhol took moments from popular culture and turned them into history, Horkay takes history and turns it into a moment, as though the past millennium was a monolithic unit of time.

István Horkay was born on 1945 Budapest Hungary. After graduating from the School of Fine Arts in Budapest in 1964, Horkay was invited to attend the Academy of Fine Arts in Cracow, Poland, the Major Art and Cultural Center of Eastern Europe, where he received his Master of Fine Arts.He continued his Studies at the Royal Academy of Art in Copenhagen, Denmark. (1968) and did additional Post graduate work atthe Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest. (1971) Horkay studied under the Internationally known Artist and Theater Director Tadeusz Kantor as well as Professors M. Wejmann and J.Nowosielski. and Palle Nielsen (Denmark) He received Diplomas in Graphic Arts, Painting, and Film Animation.

read more »

May 02, 2004 From: HAYNERART

Horkay, he is the KING

www.haynerart.com

Photographe, de studio à Paris : pack-shot, catalogues, objets (luxe, bijouterie, horlogerie), cosmétique, culinaire, reportages et portraits.Photographe Studio, Paris, bijoux, bijouterie, objets, pack shots, reportage, culinaire, image, illustrations

www.phane-photographie.com

In "Ten Years After: The Warhol Factory" the artistic achievements of six of Warhol's associates are featured. Gerard Malanga, Billy Name,.Ultra Violet,.Allen Midgette and Christopher Makos are included in the exhibition, as well as Warhol's nephew, James Warhola, who carries on the artistic tradition within the Warhola family. Laura Rubin joins the artists of the Warhol Circle with select photographs from the factory years. This multimedia exhibition examines the artistic and cultural achievements of six living artists, who first gained prominence through their association with Andy Warhol, and who continue to practice their arts to the present day. The group comprises several generations of Warhol's associates. It begins with those who played an integral role in founding the famous silver Factory in the early 1960's (Gerard Malanga and Billy Name) and those who were attracted to Andy and his studio in the early years (Ultra Violet and Allen Midgette); extends to one who entered Warhol's circle after his move to Union Square in 1968, and then to the final location on 33rd Street (Christopher Makos); and concludes with Andy's own nephew (James Warhola), who carries on the artistic tradition within the Warhola family. Each artist is represented by a mini-retrospective of ten works, surveying the varied media and phases of his or her career. These include themes of human sexuality (homosexual, heterosexual, transvested); spirituality (Christian subjects and Zen philosophy) and death and disaster (guns and car accidents); a fascination with famous people and Native Americans, with physical beauty and international travel, and with conceptual art and its progenitors (especially Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray and John Cage); the union of word and picture (in concrete poetry, and in poetic/photographic memoirs); and the appropriation and replication of images (through photography, photo silk screening, and photocopying). Laura Rubin joins the artists of the Warhol Circle with select photographs from the factory years. read more »

www.audartgallery.com

Simple Kid is a walking, talking, falling down pop paradox. the sharpest, most complex, poisonous, saddest and funny lyricist trading under a flimsy disguise of idiocy

Simple Kid #1 : With interest in the likes of Drake and Buckley being invigorated in recent years, there has been a surge in the number of troubadours in the music world. While most seem to happily follow the footsteps of Messrs Drake, Buckley (x2) and Dylan, Simple Kid embellishes his influences with his own experimental samples and insightful, unique lyrical style. Imagine Dylan and Badly Drawn Boy fighting with Casio keyboards and you start to get the idea. Standout tracks such as 'Staring At The Sun' and 'Average Man' are thrilling and joyous, and the rest of the songs are great fun. An assured debut that is not afraid to be different, and promises much more in the future.

read more @ amazon »

Pierre-jean Grouille - independent Parisian Photographer - delivers to you his personal and contemporary vision of the world which surrounds us.

read more »

My name is Kevin and I'm a 30-something guy from the Toronto, Canada area. I live just north of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. I'm a nature nut and enjoy getting outside with my camera every chance I get. I love to travel. I've been across Canada, many parts of the US, the Bahamas, Germany, and Egypt. The trips next in line for me will be Scotland, Australia, New Zealand, and Nepal. My camera bag contains a Canon EOS digital Rebel, along with a few lenses (Tamron 90mm macro, Canon 24-85mm USM, Canon EF-S 18-55mm, and a Sigma 70-300mm DL macro super). Photography has strictly been just a hobby to get me outside into the fresh air (although I have had a photograph featured in "Wolves" magazine in the spring 2002 issue. I also have had one of my photos featured on a musicians CD package). I have no training or the patience to take a class in the art of photography. I like to just learn by trial and error (heavy on the error).

read more »

Contemporary Abstract Artist Painter Fine Art Abstraction read more »

www.vincenzobalsamo.com

Nature Photography

www.simonvacherphotography.com

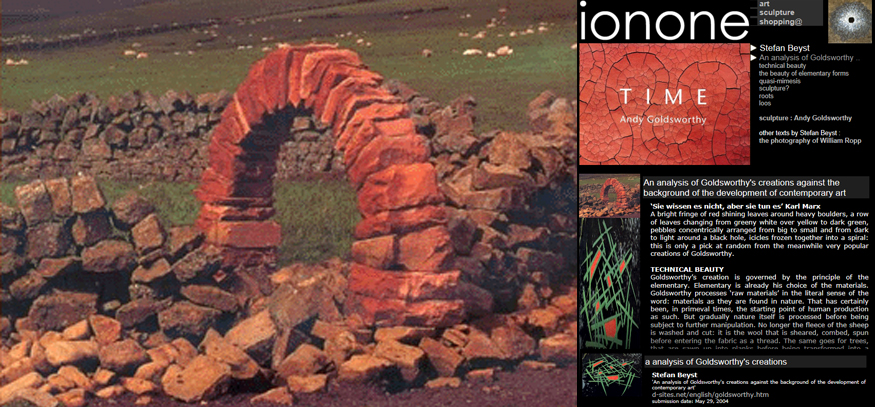

‘Sie wissen es nicht, aber sie tun es’ Karl Marx

A bright fringe of red shining leaves around heavy boulders, a row of leaves changing from greeny white over yellow to dark green, pebbles concentrically arranged from big to small and from dark to light around a black hole, icicles frozen together into a spiral: this is only a pick at random from the meanwhile very popular creations of Goldsworthy.

TECHNICAL BEAUTY

Goldsworthy’s creation is governed by the principle of the elementary. Elementary is already his choice of the materials. Goldsworthy processes ‘raw materials’ in the literal sense of the word: materials as they are found in nature. That has certainly been, in primeval times, the starting point of human production as such. But gradually nature itself is processed before being subject to further manipulation. No longer the fleece of the sheep is washed and cut: it is the wool that is sheared, combed, spun before entering the fabric as a thread. The same goes for trees, that are sawn up into planks before being transformed into a piece of furniture; for the grain, that after having been submitted to cultural selection is previously ground to flour before being baked into bread; for the clay that is previously moulded into the shape of bricks and baked before entering the masonry. Not so with Goldsworthy: his colours are not just squeezed out of a tube. It are the very colours you just find like that in an autumn forest. They are all over the place. Just like sticks, pebbles, plumes, icicles and all the other materials Goldsworthy is using. Found materials, thus, that deserve an equally elementary processing. In most cases Goldsworthy limits himself to the selecting, displacing or rearranging of leaves, pebbles, sticks and boulders. When he uses instruments at all, then equally ‘found’ instruments: the stick wherewith he scrapes the sand, the thorns wherewith he sticks the leaves together. More often, he lets nature work on its own without the intervention of any instrument: as when he lets icicles freeze together. And also in this cases the forces of nature are not previously isolated and boosted, as is the case with the heath of the fire in an oven. Goldsworthy rather lets his clay dry in the sun. Sometimes the processing is negative: as when man-made stones of sand are dismantled through the tide, or when a snowball collapses when melting, or when the clay enveloping boulders bursts during the process of drying. And equally minimal is, finally, the composition created by Goldsworthy. Goldsworthy replaces the variegated chaos of leaves in the forest or pebbles on the beach with a progression from one colour to another, from light to dark, from big to small, or with a coordination in identity. He replaces sticks fallen at random on the ground with a circle, or a line. What is laying down on the earth - the ultimate fate of everything susceptible to gravity - Goldsworthy piles up to cones, towers, or even arcs, domes and eggs struggling against gravity. Sometimes the same effect is obtained through a mere shift of the direction in which nature had formed her materials: icicles pointing vertically in the skies or protruding horizontally from a rock face – or turning around themselves in a spiral. Thus contrasted as found versus created order, Goldworthy’s creations profile themselves as artificial figures against a natural background. But the new order is not unnatural as such, it is so only in the given context. Lines, cracks, meanders, spirals, concentric forms or chessboard patterns, star-shapes, spheres and eggs: these are all compositions that can be found in nature, but applied to other materials in other contexts. Goldsworthy himself reminds us of that when his composition explicitly refers to other natural phenomena: as when he imposes the spiral-shape of the nautilus shell on leaves. Sometimes Goldsworthy’s composition is so deceptively natural that we might inadvertently pass it by. That something has been photographed, makes us suspect that there is something to be seen: a mere crack running right through a whole series of pebbles. Until it dawns on us that single pebbles may well crack, but possibly not an entire row! Only then do we realise that the supposedly natural crack is in fact a composition borrowed from nature and imposed upon a series of broken pebbles. In all cases, Goldsworthy realises a maximal effect, precisely by refraining from isolating his creations from their natural soil. Precisely the untouched virginity of the environment makes the creation visible as a disturbance. That is why nature is not only the provider of raw materials, techniques and processing, but foremost the natural biotope of Goldsworthy’s creations. Transported into an artificial environment, they would lose all their charms. Also in this sense do his creations remain bound to nature by an indissoluble tie. And that brings us to the meaning of such creation. Goldsworthy is not out at the mere production of a useful object, let alone an object that should please man for its sole beauty. He wants rather to embody the beauty of the act of creation in an exemplary intervention. That is why the often irresistible charm of his work does not derive from the final result, but from the beauty of its creation, the deed to which its owes its existence and that remains visible in the end product. This kind of creation strikes the all too often disturbed chord of harmony with nature: man is allowed to intervene, to bend to his will, even to disturb, but not to rape, let alone to saw off the branch of the tree on which he is sitting. The technical beauty of Goldsworthy’s work can be read as a silent criticism on the industrial and post-industrial way of production, which no longer processes materials that have been found in nature, but materials that have been submitted to an often endless series of transformations for them to subdue without any resistance to the forces of nature unleashed by man in super-instruments and machines. As when the laser cuts thick steel plates without any resistance, not to mention the silent violence wherewith in the digital dimension quantities measured in megas and gigas are digested in fractions of seconds. Precisely the astounding ease wherewith every resistance is eliminated beforehand, results in the scaling-up that, already from the pyramids onwards, foreshadows the ultimate tower of Babylon: it is the awe-inspiring ugliness of many a architectural giga-project, that in its monstrous proportions is knocked up in a few months or of the hideous vehicles that in many a science fiction film are released in space. Goldsworthy’s silent criticism is all the more charming since it speaks through the work itself and is not added to it through some external symbolism. No references to Indians, Zen or yin and yang come to spoil or fun.

THE BEAUTY OF ELEMENTARY FORMS

We would do no justice to Goldsworthy’s work when reducing it to an embodiment of a harmonious relation to nature. Next to the pleasure in technical beauty, there is the pleasure in the beauty of the forms that are created through such harmonious creation. Of old, man has shown a predilection for forms with a transparent structure: that is what is so charming about straight, curved or broken lines, circles, crosses or chessboards and geometrical patterns in two or three dimensions. As when in the centre of a concentric form there appears a dark hole. Which fascinates, not only because it reminds of the pupil of the eye that already always steals our attention, but also because of any hole we want to know what it hides – a curiousness that often is accompanied by fear for whatever might show up: hence the aura of mystery hovering over Goldsworthy’s holes and concentric structures. Sometimes Goldsworthy soothes the anxious tension through filling it in: in the hole an object in the form of a spiral is coiling like a caterpillar in its cocoon, or a trees grows out of it, or a rocky point is poking out of it.

QUASI-MIMESIS

The formal beauty of a concentric form as well as the emotional freight of an encircled hole do not differ from the effect of similar phenomena in nature. The only difference is to be found in the maker: nature or man. But in some of his works, Goldsworthy is doing more than merely creating a new reality alongside nature. Now and then, it seems that he tries to imitate an already existing reality: as when a three-dimensional spiral reminds of a nautilus shell. Or when concentrically woven sticks remind us of a birds nest or an eye. Or when sticks with burned tops are arranged in the shape of a cone and then remind us of a volcano. Or when a fringe of red shining leaves surrounding black boulders remind us of burning rocks. Or when mandorlas remind us of eyes, mouths or vaginas. Or when the crack in a row of broken pebbles remind us of the cracks in dry clay. There are also more ambivalent cases where the ‘reminding of’ is rather a recreation. As when amidst some real rocks one single rock is enveloped in weather-beaten branches, sun-bleached bones or pieces of bark. Such ‘reminding of’ is mimesis in statu nascendi. It differs from full mimesis in that we only are ‘reminded of’ something else. We never have the impression of seeing something else as what there is to be seen. It was not Goldsworthy’s intention to evoke a birds nest, bur rather to realise around the hole in the roots of a knotty tree the concentric shape for which it seemed to ask. Where such quasi-mimetic dimension joins technical beauty and its critical-utopian dimension, as well as the formal beauty of the form and its emotional freight, a tension is created between the multiple layers of the work, contributing to a deeper resonance of the whole.

SCULPTURE?

But it makes also clear why it is misleading to call Goldsworthy a sculptor – be it an ‘environmental sculptor’ or a ‘sculptor/photographer’. Not that the materials prevent us to do so. It is not because Goldsworthy does not use traditional materials that he would not be a sculptor: three-dimensional sculpture can be made in whatever material. Whether one belongs to the tradition of Praxiteles, the master of the Western portal at Chartres, Sluter, Michelangelo, Bernini, Rodin or Moore – not the mention the countless masters from other cultures – does not depend on the materials used, but on whether the intervention of the artist transforms his material in something else: like the marble that, under the hands of Michelangelo, is transformed into the flesh of a body, or under the hands of Bernini in the mantle of Saint Theresa. Everyone will agree that such is not Goldsworthy’s intention, even if some of his creations ‘remind of’ something else. No: Goldsworthy creates real things that do not at all pretend to be something else. That is why he belongs in the world of all those who transform nature into ‘humanised’ nature: from the cook, over the designer of clothes and furniture, gardens and parks, automobiles and machines, to the architects. To be more precise: Goldsworthy belongs to the tradition of garden architecture: from the geometrical renaissance gardens, over the romantic English gardens, to the mystic pebble-gardens of the Japanese, or their modern counter-parts: the ecological landscape. Witness the ‘Sheepfolds Project’ in Cumbria, where Goldsworthy rebuilds in a more artistic fashion the walls formerly built by shepherds. Or we can situate him in the tradition of the more small-scale art of flower arranging (ikebana). But within this group of ‘artists of design’ – designers to call them by their name – he distinguishes himself – just like other giants like Panamarenko – in that he does not contrive functional objects, but objects embodying the mere pleasure of making them – and a sympathetic kind of making at that: creating in harmony with nature. That is why Goldsworthy may justifiably be called the master – the artist – of free creation. Which does not prevent that he is not a master of ‘imitation’ – not an ‘artist’ (or 'sculptor’) in the traditional, more limited meaning of the word. Which does not mean that we should condescendingly look down on him. On the contrary: the designer of the cathedral is no lesser god than Van Eyck. But the former is a ‘master of design’ – a master in transforming nature into a product that provides in human needs – the latter is a master in the transformation of oil paint into a mere represented world. And, to distinguish both kinds of master from each other (and from other masters such as the masters in philosophy or in making love), it would be better when we called the former ‘designers’ and the latter ‘artists’.

ROOTS

Which does not prevent that a thorough understanding of Goldsworthy’s work is only possible against the background of the development of art in the twentieth century art. It has no roots whatever in the history of design. To begin with, there is a certain relation with the Duchamp’s ‘ready mades’, or rather: with the ‘objets trouvés’ of surrealism. That is why we talked about ‘found materials’, ‘found techniques’ and ‘found processing’ above. Next, Goldsworthy’s work is unthinkable without the so called ‘land-art’ from the seventies. As an offshoot of the happenings and the performances of the sixties, this movement represented a particular version of the ‘dissolving of art into life’: the replacement of conjuring up an imaginary world through real transformation of the real world – in this case: nature. It suffices to refer to the works of Richard Long, who equally limited himself to minimal interventions in the landscape and whose works equally became popular through equally popular books. At the roots of land-art lies the anti-capitalistic gesture of those who were no longer prepared to submit to the logic of the market. It was their intention to free art from the ‘art shops’: the galleries. One of the places where art was to be accommodated was nature, where it would be freely accessible to everyone – and where everyone could create it as well. The descent from land-art equally explains why Goldsworthy is deliberately out at creating transient works – exemplary in the use of withering flowers or melting snow. The predilection for transience is one of the variants of the mimetic taboo: the reluctance to make enduring works of art – with the concomitant obligation to measure up to the great masters, who, precisely because their works are enduring, continue to project their castrating shadows far into the future. Both strivings inherited from land-art were doomed to failure. It soon became apparent that land-art was not accessible at all. And it would be a pity to deliver such marvellous creations as Goldsworthy’s icicles to decay. That is why the anti-capitalistic and anti-mimetic land-art was fixed on photographs or videos and sold at a bargain. Albeit not in the gallery, but in the bookshop.

LOSS

The remarkable thing about all this is that of all places here, in the very bastion of modern art, we stumble upon something that has supposedly been utterly banned from it: unbroken beauty! It is only most regrettable that this beauty must bloom on a corpse: that of the art of sculpture.

© Stefan Beyst, May 2004

read more »

Sylvie Robert was born in Paris in 1964. Her love develops mostly in the areas of figurative Art (realism), first classic then contemporary. Although degreed in business administration, Sylvie has accelerated her passion for art thought the use of modern computer technology.Refining her classical and esthetic taste she has develop a fantasy vision that would make Salvatore Dali jealous as she continues her experiments in digital imagery.Her works are a fusion of dimensional speech that evolve thought time and space covering “expressionism ipormali” (ipoformal expressionism) and post realism. She mixes emotions of the purest esthetics with the timeless recognition of the evolution in technical landscape reaching the ultimate in contemporary digital expressionism. Sylvie Robert has joined the elite class of the Digital Artists Her elegant use of color combined with fluidity of forms and her originality of backgrounds (neoclassic and futuristic) will delight even the hardest critic. Owning a painting by Sylvie Robert is not only a good investment and pleasure but also a glimpse into the world of fantasy and good taste. read more »

www.sylvierobert.com

'An analysis of Yeat's 'Leda and the swan' against the background of his work and the history of art'

Whatever your stance on Yeats’ poetry, you would not deny that the man has written a poem the charms of which no devotee of art can possibly resist: the unparalleled ‘Leda and the swan’ which sounds as follows

LEDA AND THE SWAN

A sudden blow: the great wings beating still

Above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed

By the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill,

He holds her helpless breast upon his breast.

How can those terrified fingers push

The feathered glory from her loosening thighs?

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?

A shudder in the loins engenders there

The broken wall, the burning roof and tower

And Agamemnon dead.

Being so caught up,

So mastered by the brute blood of the air

Did she put on his knowledge with his power

Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?

THE TECHNICAL BEAUTY

of this poem just catches the eye.

To begin with, there is the structuring of the whole episode. The poem may be divided in two halves. The first comprises the violent encounter of Zeus and Leda ending in ‘a shudder in the loins’, whereas in the second both spatial and temporal perspectives widen into infinity.

This partition matches the division of the sonnet into octave and sestet. Which is marked through the similarity of the two bold phrasings summarising the event in its constituent elements: ‘A sudden blow’ initiates the octave and ‘a shudder in the loins’ the sestet. It also coincides with a shift in the temporal perspective. The octave is in the present tense; the first half of the sestet at once projects us in the far future ‘(Agamemnon dead’); from this vantage point we look back on the violent encounter (‘did she put on his knowledge…?’) that now is irrevocably referred to the past. And this binary structure is echoed in the grammatical construction: each half comprises two sentences, each encompassing a single strophe, the first and the third of which are affirmative, the second and fourth interrogative. The alternation of affirmation and interrogation goes hand in hand with a change in the commitment of the reader, who seems to identify himself with the swan in the affirmative sentences, whereas in the interrogative ones he seems to ask himself how Leda might experience her brutal overpowering.

Over this apparent articulation in two halves is superposed a second, this time asymmetric, binary structure. It is marked by the typography: ‘being caught up’ is referred to the second half of the sestet. In the first half of this partition the unstoppable unfolding of the proceedings is depicted into its furthest consequences: everything is rendered in the present tense. In the second shorter half, written in the past tense, the deeper meaning of the event is fathomed.

A further counterpoint to the central partition is the shift in spatial perspective. No swan is staged, but ‘great wings’, ‘dark webs’, ‘his bill’ ‘his breast’, ‘the strange heart’ ‘the brute blood of the air’ ‘the indifferent beak’. And also from Leda we only catch a glimpse of ‘her thighs’, ‘her nape’, ‘her helpless breast’, ‘those terrified fingers’, ‘ her loosening thighs’ and ‘the strange heart’. In short: a perspective familiar to all those who happen to be cast by the spell of the flesh. Only with ‘body’, but foremost with ‘the feathered glory’ and its the counterpart: the ‘staggering girl’, does the camera seem to zoom out. But it is only when we are faced with the consequences of such promiscuous entangling of body parts that we are allowed a panoramic view on the whole: ‘The broken wall, the burning roof and tower and Agamemnon dead’. Thus, the temporal partition in present and past tense is joined by a spatial partition between the more involved close up and a rather contemplative panoramic view.

As far as meter is concerned, it is apparent that the diction only unwillingly complies with the train of the iambic pentameter. We have to first witness the forceful resistance of the ‘great wings beating still’, the ‘dark webs’ and her ‘nape caught’ – an accumulation of stressed syllables wonderfully echoing the ‘sudden blow’ of the swan’s wings. But even when the metrical order seems to be restored, the asymmetry of the grammatical structure continues to oppose the regular flow on a more abstract level. Most conspicuously in that masterly - unforgettable - first half of the sestet:

A shudder in the loins engenders there The broken wall, the burning roof and tower And Agamemnon dead.

The rhythm determined by the alternation of adjective and noun as it is initiated in ‘broken wall’ and ‘burning roof’, is not carried on in ‘tower’, which has to manage without adjective. But the latter surfaces again in the consequent ‘Agamemnon dead’, albeit this time after the noun. Over the repetition in the word rhythm a second pattern determined by the alternation of adjective and noun is superposed: a rotation from initial position to end position. To the unparalleled rhetorical effect that the whole procedure of begetting life is turned into its very opposite. To which we shall return below.

Next to the word rhythm and the alternation of adjective and noun also the sonorous body of language is summoned up to evoke the encounter. Think only of the way in which ‘he holds her helpless breast’ unabashedly renders Zeus’ heaving. Not to mention the ‘broken wall, the burning roof and tower and Agamemnon dead’, the infernal sonority of which only joins the solemn stride of the meter to a veritable funeral march reminding of Wagner’s ‘Siegfrieds Tod’.

The theme

But let us first introduce the theme. The story of Leda stems from Greek mythology. Leda is the Spartan king Tyndareus’ wife. When she saw her chances, she did not hesitate to exchange her royal husband for a god: Zeus, even when he approached her in the shape of a swan. Which yielded her four eggs. Out of which not only hatched Castor and Polydeukes as well as Clytemnestra, but first and foremost the Helen of the Trojan war.

Of old, the theme has been very popular in the plastic arts. It will turn out to be very fruitful to first examine how it has been handled there.

The representation of loving couples has always been a problem in the plastic arts. For the obvious reason that of a couple intertwining – Brancusi’s animal with the two backs – the most enticing fronts are hidden from view. Literature knows not such problem. When reading Ovid’s verse ‘ Leda is lying between the swan’s wings’ (Metamorphoses VI, 109), not only do we see before our mind’s eye the pair of wings embracing Leda, but the body covered by these wings as well, not to mention the experience of the most diverse bodily sensations. In painting or sculpture, on the other hand, we are not faced with malleable representations for diverse senses, but with a concrete visual image. The painter that from the encounter of Leda and the swan would only show us the sight of spread out wings would not show at all: he rather would hide from view precisely what we so dearly wanted to see.

The classical solution consists in staging the bodies immediately before their entwining. But such is not a becoming solution in the case of Leda and the swan: we precisely wanted to witness the proceedings after the encounter! And to make a picture thereof raises a lot of problems.

To begin with, there is the tension between the impressive figure of Zeus and the rather humble shape of the swan wherein he is transformed. Especially since the little bird also has to mount the huge female body. Before the mind’s eye we inconspicuously adapt the shape of the swan, as with the already cited verses of Ovid. But when the scene is graphically depicted there before our very eyes, the discrepancy between the mighty Zeus and the rather humble shape of the swan catches the eye. It must be granted, though, that the very same humble shape also yields an unexpected gain: the beast with two backs has on one side exchanged a broad back with a slender neck, to the effect that nothing any longer prevents the full exposure of Leda’s enticing front (see Corregio’s Leda, 1530, Berlin Dahlem).

But whoever might reconcile himself therefore with the humble elongated shape of the swan, cannot possibly let it pass for the mighty Zeus. Unless he focusses on Zeus' mighty member: only of this true Adam can the swan be the becoming metamorphosis – the long neck then stays for the stem of the penis, the head for its glans, the winged trunk for the scrotum. And such life-sized organ cannot fail to head straightforward towards its goal: also in the real world the stretched out neck of a swan reaches to the genitals of a woman standing. Although the beak of a real swan, as opposed to that of reckless goose, happens to rather modestly bend downwards.

La figura serpentina

Of course, the painter might proceed to adapt the shape of the swan to Leda’s body. But he then faces new problems. To begin with, also the wings grow accordingly - and they come to stand higher at that. Would we let them play the role of the lover’s arms embracing his beloved, her beauty were hidden from view by a pair of wings again. Far more interesting, then, to let them flap and express the superior strength of the swan. The task of subduing Leda’s body is then relegated to the beak which has to catch Leda in her nape. This solution has been chosen in the Hellenistic relief above. The swan’s body, running out in the slender neck, no longer embodies the erect member, but the entire body of Zeus. To the effect that the penis is relegated to the lower regions where it is reduced to its former proportions. But there again it comes to face still other problems. Although of all the winged beings the swan has perhaps the biggest penis – rather: something that can be called a penis – it does not end up in a vagina, but in an arse – and that was not precisely what Zeus was after. In the Hellenistic relief the dorsal approach implied by the catching in the nape is replaced with a frontal one, as is more becoming to men – let alone gods! But the swan seems not to be able to cope with the frontal approach: Leda has to adjust something or other with her hand! The frontal twist in the lower regions finds its counterpart in a dorsal twist in the higher spheres, were the slender neck graciously bends downwards to catch Leda’s nape from the back. To the effect that the swans’ webs are no longer stamping on a feathered swan’s back, but on Leda’s white thighs. Also on the Roman representation below, where the artist has equally chosen for blowing up the swan, the focus is on the proceedings in the genital zone. And also here things seem not to work properly: Leda has to pull the swan's legs to get things straight. So, only after some considerable twisting, turning and adjusting can they find each other, Zeus and Leda.

In the ancient representations, the focus is on the problematic nature of the encounter of beast and man. We have to await the heathen Renaissance to witness a deepening of the approach and the corollary invention of more convincing solutions.

Da Vinci's Leda

It is da Vinci (1452-1519) who sets the tone for the new approach. In his first drafts of the theme he tries to solve the problem of the shape by letting Leda bend, as parents do when trying to adapt to the small stature of their children – or Mary when kneeling before her holy son. But on the eventual painting (only known through its copies), Leda is standing again, and she is approached by the rather impressive swan on her side.

The interesting thing is that, in both versions, the beak no longer reaches to the navel, but to Leda’s very lips. It is no longer out at penetrating the vagina, let alone to catch Leda in her nape: its declared aim is bluntly Leda’s mouth. One of the formerly flapping wings now gently embraces Leda’s hip. And such entwining does hide nothing from view. On the contrary: since the encounter has shifted upwards, Leda can be taken under the arm from behind, to the effect that her magnificent front remains visible in all its splendour. It appears that the oral approach meets some resistance: although Leda willingly coils herself in the swan’s wings and turns her breasts toward the swan, she teasingly withdraws the lips in her face. And the same goes for the hesitating hips and her hanging leg.

Michelangelo's Leda

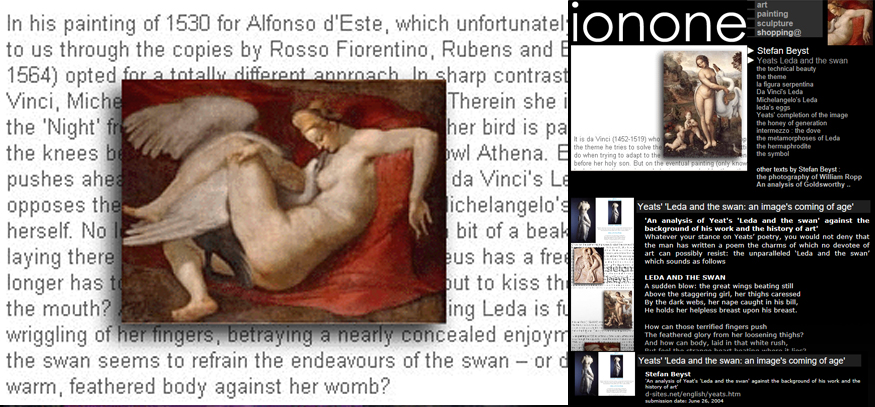

In his painting of 1530 for Alfonso d’Este, which unfortunately enough has only come to us through the copies by Rosso Fiorentino, Rubens and Bos, Michelangelo (1475-1564) opted for a totally different approach. In sharp contrast with the Ancients and da Vinci, Michelangelo has his Leda lying supine. Therein she is a further development of the ‘Night’ from the Medici chapel – where another bird is paying his respects under the knees before the entrance of the gate: the owl Athena. But Michelangelo equally pushes ahead with da Vinci's innovation. While da Vinci’s Leda rather modestly opposes the indecent proposals of the swan, Michelangelo’s willingly abandons herself. No loonger needs she to be forced by a bit of a beak in her nape: she is laying there for the kissing. To the effect that Zeus has a free neck: his beak no longer has to catch Leda in her nape, his is about to kiss the lips – or to penetrate the mouth? And the complicity of the half-sleeping Leda is further emphasized by the wriggling of her fingers, betraying a nearly concealed enjoyment. Only the right arm of the swan seems to refrain the endeavours of the swan – or does it rather press the warm, feathered body against her womb?

And that reminds us of the fact that Michelangelo’s swan is granted its natural proportions again. Which induces it not only to penetrate the mouth with its beak, but also the vagina with its penis: it suffices to get a glimpse on the position of the tail, which is spread like a fan over the vagina and the black web bluntly plopped down on the soft inner side of Leda’s white thighs. Although the dark tone of the tail may be motivated through its position in a shadow zone, it first of all seems to be the emanation of what it conceals: the black penis of the swan – vicariously made visible in that equally black web. Also another colour has shifted to the periphery: the red of the equally concealed vagina. The red draperies whereon Leda is spread are the nearly concealed representation of a vagina (see also the print of Bos). Not only Michelangelo is fond of making rather obscene representations shimmer through seemingly neutral draperies...

Thus, da Vinci’s swan as well as Michelangelo’s is resolutely turning perverse. But both masters immediately keep it on the straight and narrow. With this conflict corresponds the ambivalent filling in of the body of the swan. Although da Vinci’s swan takes the shape of a full-fledged human body, Leda only has to disappointedly turn away from a void, while at the same time the swan’s greedy beak is deliberately out at her lips. And even when Michelangelo’s swan remains a small bird, not only does its agitated body stubbornly try to penetrate the vagina, even more eagerly does the greedy neck edge its way between the breasts toward the mouth.

Leda's eggs

The perverse move away from the genitalia to the neck and the beak finds its counterpart in the equally perverse move away from fertilisation and birth. No longer do penises or vaginas come to spoil the fun of begetting. And with birds also birth is no longer a question of repugnant slime, but a clean affair of white shells: the immaculate conception of the white egg (see: ‘La Cane et son omelette', forthcoming’).

And that holds especially for our story. The four children springing from the encounter of Zeus with Leda were not precisely born, they rather hatched out of eggs. Already in his drafts does da Vinci throw Leda her offspring in the face. With Michelangelo, where the swan is nevertheless rather busy down there, no eggs are to be seen, at least on the copies of Rosso Fiorentino and Rubens. On the print of Bos already one egg has hatched and another one on the foreground is on the verge of doing so.

Even when the emphasis on the consequences of the deed is in line with the genital-fertile defence against the perverse proceedings of the swan’s neck, the fact that birds have to do without a penis and a vagina perverts their reproductive efforts from within.

And that equally holds of Yeats. Even when no eggs are mentioned in his sonnet, in ‘Among school children’ the poet stages a ‘Ledaean body’ wherewith he feels united as ‘the yolk and white of the one shell’. And that reminds us that we are dealing here with Yeats’ Leda. But only now are we ready to tackle the sonnet properly.

Yeats' completion of the image

According to Charles Madge* the above mentioned Hellenistic relief would have inspired Yeats. Which is evidenced by the flapping of the wings, the emphasis on the web on Leda’s thighs, but foremost by the way in which the swan catches Leda’s neck and presses her face against its breast.

But equally right are all those who traditionally maintain that the poem is inspired by Michelangelo’s Leda. To begin with, Yeats’ Leda does not stand upright, as she does on the Hellenistic relief. She is lying supine, as with Michelangelo. And even when the webs on Leda’s thighs may also appear on the relief, marble has no colour, and it is precisely the resonance of that colour black that is more than echoed in that splendid ’her thighs caressed by the dark webs’. But foremost those ‘terrified fingers’ betray that also the painting of Michelangelo lies at the roots of Yeats’ sonnet. Even when they ward off, rather than wriggle out of pleasure. The mere fact that Yeats’ Leda uses frail fingers rather than full arms to ward off the brutal swan, at once reminds us of the fact that also on the Hellenistic relief Leda does not ward off. With her full arm she rather eagerly extends a helping hand – her wriggling fingers being hidden from view through the thighs.

It is apparent, then, that Yeats must have been strongly impressed with the greediness of Michelangelo’s swan and the complicity of his Leda, but foremost with the eagerness wherewith the Hellenistic Leda helps the swan reach its goal. Which does not prevent that this erotic fervour equally unleashed a strong counter-current in Yeats. Which departs not so much from the proceedings under Michelangelo’s fanning out of the tail, as rather from the more convincing proceedings between Leda’s thighs on the Hellenistic relief. Through such regression from the ‘Renaissance’ to ‘Antiquity’, the pushy beak that effortlessly reaches its goal, is whistled back to the place where it belongs: between the thighs. And to seal the genital metamorphosis Yeats also borrows the most striking gesture of the Hellenistic relief: the compelling force wherewith the swan catches Leda in the nape, which neutralises the organ of lust into a mere instrument. And the crowning glory of this work are those ‘terrified fingers’, wherein Yeats utterly negates the seemingly denied complicity of da Vinci’s Leda and the nearly concealed complicity of Michelangelo’s Leda.

It seems as though Yeats reduces the ambivalence between perverse and fertile strivings to the sole genital proceedings. The scale seems to resolutely tip in the direction of the pole of negation. In line with this negation Yeats stresses the reproductive consequences of Leda’s encounter: the ‘shudder in the loins’ ‘engenders’ – an echo of da Vinci’s emphasis on Leda’s eggs.

The honey of generation

But that very ‘engenders there’ following the ‘shudder in the loins’ puts a heavy damper on the triumph of the member foolhardy. What is begotten there is not precisely suited to welcome the deed of procreation: whoever would like to be the father of ‘the broken wall, the burning roof and tower and Agamemnon dead’? Which of course is a reference to the Trojan war waged on occasion of the unfaithfulness of Helen, one of Leda’s chicks. The fratricide is represented through another pair of chicks: Castor and Polydeukes. Also on da Vinci’s painting the hardly hatched mortals are already attacking each other. And the role of the fourth chick is played by Agamemnon, who was murdered by Helen’s (twin) sister Clytemnestra (in Aeschyles’ version).

In that ‘Agamemnon dead’ resounds still another reproach to the deed of begetting. In ‘Among schoolchildren’ Yeats complains the ‘youthful mother’ ‘honey of generation had betrayed’:

What youthful mother, a shape upon her lap (...)

that must sleep, shriek, struggle to escape (...)

Would think her son, did she but see that shape

With sixty or more winters on its head,

A compensation for the pang of his birth

Or the uncertainty of his setting forth?

What the honey-sweet ‘shudder in the loins’ engenders, is not so much life, rather death. Not to mention all those minor burdens that the poor mortals lift on their shoulders for the lust of one moment’s sake. In the short term the ’pang of birth’. In the somewhat longer term: the care for their progeny ‘that must sleep, shriek, struggle to escape (…)’. And at long last the growing realisation that all these offers have been in vain: we only beget to doom to death. For the sole taste of honey’s sake!

No wonder that love recoils in the face of such dreadful perspective! Yeats, though, never speaks out this truth. He rather prefers to state without any further explanation that love is merely an transient transport – or to phrase it with Schopenhauer: a cunning of nature that is merely out at eternal reproduction. Time and again Yeats stresses the transience of love. In ‘Never give all the heart’ he holds that:

it fades from kiss to kiss;

for everything that’s lovely is,

but a brief, dreamy, kind delight

That is precisely why he warns us ‘Never give all the heart’. With as an encore:

‘He that made this knows all the cost,

for he gave all his heart and lost’

Which of course causes the soul to leave her limbs, as in ‘The lady’s second song’:

Soul must learn a love that is

Proper to my breast,

Limbs a love in common

With every noble beast.

Which again sheds a new light to the swan as ‘the noble beast’

Intermezzo : the dove

Also in ‘the Mother of God’ a woman is impregnated by a bird, equally ‘wings beating about the room’. Although this time it is a dove, and although this time not a daughter is hatched, but a son. Destined to death by his very father…

What is this flesh I purchased with my pains,

This fallen star my milk sustains,

This love that makes my heart’s blood stop

Or strikes a sudden chill into my bones

And bids my hair stand up?

Herein Yeats joins a tradition that we swept under the carpet to allow ourselves a rapid transition from Antiquity to the Renaissance. But just as only as a metamorphosis of Mary Venus is reborn on Botticelli’s painting, just so the genuflection of da Vinci’s Leda before her eggs is a nearly concealed echo of Mary falling on her knees before her son Jesus. Who was brought to the world to redeem us of the sins of precisely the fratricidal twins that hatched from the swan’s eggs…

The metamorphoses of Leda

Indulging in the kind of love he has in common with ‘every noble beast’ leads to man’s fall. The endeavour to break the fall unleashes the perverse move. The tempestuousness wherewith the unruly procreative violence, embodied in the flapping of the wings of dove and swan alike, is enforcing itself, unleashes an even stronger unwillingness to surrender. For only at first sight does Yeats negate Renaissance’s perverse strivings. In fact Yeats faces us with the central conflict that sets alight the perverse fire, while at the same time allowing the perverse counter-move to expand in ever wider circles.

To begin with, Leda is overpowered by a ‘noble beast’ and not by a mere man or god. The metamorphosis of man into bird releases the male of precisely the source of all evil. And even when Yeats neutralised Michelangelo’s greedy swan neck to a compelling beak, the perversion literally returns through the back door: the catch in the nape implies an approach from behind. In ‘Crazy Jane talks with the Bishop’ (Words for Music Perhaps, VI) Yeats himself betrays what is performed there in the lower regions as the counterpart of the ‘nape caught in his bill’ and under the guise of a ‘shudder in the loins’:

Love has pitched his mansion in

The place of excrement.

The obliteration of the penis is completed by the vagina’s metamorphosis into a cloaca.

But the repressed returns not only through anal channels. The process of desexualising strides further along a path that also here has been paved by painters. Michelangelo’s Leda is completely naked. The impression of nakedness is only enhanced in that Leda’s hair is covered with a skin-coloured headgear. And neither is there left any trace of the pubic hair: it is covered by the fan of the swan’s tail. Which only enhances the contrast between the white-feathered body of the swan and the utterly naked body of Leda. But the very sharpening of the contrast unravels a secret affinity. Precisely because Michelangelo smoothes away the difference between naked skin and hair, it all the more comes to catch the eye that Leda’s body ends up in a horny headgear – a nearly concealed echo of the way in which the feathered swan’s body changes in the horn of the beak. Such surreptitious assimilation of the ‘Ledaean body’ is further enhanced through Michelangelo’s emphasis on those wriggling fingers and those remarkably agile limbs. Also da Vinci’s Leda seems eager to become a swan: he lets her whole body – la figura serpentina – balance in opposite directions alongside diverse axes. An echo of the above described convolutions that had to be performed to make Leda’s and the swan’s body match?

But the metamorphosis of Leda in a swan does not halt with the smoothing out of her hair and the voluptuous posture of her body: Leda also lays eggs. That seems to go for itself. But on a closer look we would rather expect eggs when a human male impregnates a female bird. When, conversely, a bird impregnates a woman, it would be more obvious that she would cuddle little swans in her womb, until at last little swan beaks would protrude from the vagina rather than children’s heads – in a variant of the story it is Nemesis that lays the scorned eggs… after her previous transformation in a goose. Not only in her alluring demeanour and her voluptuous gestures has Leda become a swan, her metamorphosis comprises her organs as well: she lays eggs and has become a bird. The metamorphosis from vagina to cloaca was only a prelude to the metamorphosis from mammal to winged bird, the sequel to Zeus’ becoming a swan.

The hermaphrodite

Also Yeats seems to be ridden by the desire to smooth away every difference between the swan and Leda. The metamorphosis of the loving couple into a couple of birds is an old dream of Yeats’. Does he not sing in 'The white birds':

‘For I would we were changed to white birds on the wandering foam: I and you!’

With Yeats, the smoothing away of the difference between man and animal seems to encompass the smoothing away of the difference between man and woman. An obvious solution is their metamorphosis into a swan. It is rather impossible to tell a male swan from a female: both share a virginal front. And that sheds a new light on the fact that it is Zeus that presses Leda’s breast against his: ‘he holds her helpless breast upon his breast’. On the Hellenistic relief Zeus does not press Leda’s breast against his breast but Leda’s face. And this is also the case in a former version of the first quatrain:

A rush, a sudden wheel, and hovering still

The bird descends, and her frail thighs are pressed

By the webbed toes, and that all-powerful bill

Has laid her helpless FACE upon his breast.

Leda’s face upon Zeus’ breast: this immediately reminds us of a mother breast-feeding her child. But it is not Leda who breast-feeds Zeus as on Bacchiaca's painting above. It seems as if through his metamorphosis into a swan Zeus is at the same time turned into a mother. As if the desire of the mouth, that the beak had to give up to catch Leda in the nape for copulation’s sake, surfaces again in the shape of the nipples growing out of the breast of the swan – which, otherwise than with mammals, shows no sexual difference between male and female.

But Yeats must have been equally disturbed by the difference between mother and child as by the difference between man and woman. That is why in the second version is restored the reciprocity that previously existed between beak and lips: Zeus no longer presses Leda’s head against his breast, but her breast against his. To be more precise: his breast without breasts against Leda’s breast with two breasts. And to also smooth away this last asymmetry, they both feel the same in that region: if not each others bosom, than at least each other heart beating!

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?

Which immediately reminds us of the already quoted verses from ‘The lady’s second song’:

‘Soul must learn a love that is

proper to my breast,

limbs a love in common

with every noble beast’

Whereas on the level of the limbs protrusion and hole oppose each other, on the level of the soul two hearts feel each other beating. From beast to breast, the journey goes through three stations: from sperm, through milk, to blood. From the feeding breast to the beating - pumping - heart: such shift is indicated in the already cited verses from ‘The mother of God’ where Mary complains about her godly son:

This fallen star my milk sustains,

This love that makes my heart’s blood stop

A similar shift is at work in Luca della Robbia’s Leda, where the swan is not out at Leda’s breast, but rather at the place beneath it where Christ shows his wound:

And that is how Leda turns into something of a Jesus Christ. Who in his turn is often represented as a pelican feeding his young with the blood flooding from his heart – the very reversal of the image of Mary with the divine child on her breast. It seems as if we are landed up in a veritable whirl of the sexes and the generations.

But there is more. The first version sheds a new light on some oddities in the second version, that otherwise might have inadvertently escaped our attention. With the image of a swan descending from heavens in mind, we are ready to read the ‘in’ in ‘laid in that white rush’ as a ‘by’. But that very same ‘in’ cannot fail to suggest that it is not the swan, but Leda who descends from heavens ‘in that white rush’. And that lends only its full weight to the wording in the second quatrain of the first version where Leda is bluntly laid ‘on’ that white rush:

How can those terrified vague fingers push

The feathered glory from her loosening thighs!

All the stretched body's laid on the white rush

And feels the strange heart beating where it lies.

In line with such increasing osmosis of the sexes lies a second shift. In the first version ‘body’ refers to Leda’s face pressed on Zeus’ breast . But in the second version ‘body’ refers to the embracing bodies as such - Leda’s body as well as the body of her swan:

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?

The incipient metamorphosis of Leda turns out to be the mere prelude to a further metamorphosis: Zeus’ transformation in a woman/mother and Leda’s concomitant transformation in a man. Or to be more precise: both come to partake of the hermaphrodite by incorporating each other. And hence can eternally entwine, like Aristofanes spherical beings, hinted at in the verses:

‘For nothing can be sole or whole

that has not been rent’

which – significantly enough – immediately follow the already cited ‘Love’s mansion in the place of excrement’ (Crazy Jane and the Bishop). Also in ‘Among School Children’ the reunification in the egg is described: ‘

and it seemed that our two natures blent,

into a sphere from youthful sympathy,

Or else, to alter Plato’s parable,

Into the yolk and white of the one shell

The hermaphrodite is only a figure of the denegation of multiplicity as such. Its completion is the self-sufficient solitary – the one and only God – hinted at in ‘A prayer for my daughter” where ‘the soul’ learns at last

that it is self-delighting,

Self-appeasing, self-affrighting,

and that its own sweet will is Heaven’s will;

The symbol

And so we have laid bare all the roots and ramifications of Yeats’ magnificent image. It appears that Yeats has with unparalleled mastery condensed the central conflict of human existence, far more concisely - since brought to a head - than da Vinci and Michelangelo.

With this reading in mind, many an accepted interpretation rather evaporates. Foremost Yeats’ own interpretation. He believed that the age of democracy was going to its end and that a government ‘from above’ would be installed to subdue the anarchic masses, as in Russia. But Yeats himself betrays how, when working on his Leda, he was so caught by the image of the bird and the girl, that ‘all politics went out of it’ (Cullingford). And we readily believe him. Did he not write himself (in ‘Politics’):

How can I, that girl standing there,

My attention fix

On Roman or on Russian

Or on Spanish politics?

And the same holds of other interpretations: from the Platonic, through the Nietzschean, the… , to the feministic (Cullingford). Idem for the interpretations of Michelangelo’s Leda. Whatever might have been the meaning intended within the context of Alfonse d’Este’s diplomacy (Wallace), every attempt to reduce the meaning of this work to mere diplomatic symbolism would overlook that already da Vinci had introduced the new theme within a totally different context. Here we stumble on the ‘immanent’ lecture of genuine art, which is out at throwing off the yoke of symbolism laid upon its shoulders (see: 'Are Rubens and Beuys colleagues?').

Which did not prevent Yeats from giving a transcendental twist to the very image he so brilliantly knew to bring to a head and at the same time to amplify. Did he not let it end on the question: ‘Did she put on his knowledge with his power?’ Whereby he caused his creation to become vulnerable: after all no human creation is perfect. We already described how a second asymmetric partition overlapped a first symmetric one. Were it not for the overall rhythm of the sonnet to ask for its further unrolling, the breath of Yeats’ image has irrevocably breathed its last when also Agamemnon has given up the ghost. Perhaps a vague consciousness of such a rupture induced Yeats to typographically separate the second half of the last verse of the first half of the sestet and to refer it to the last – ‘added’ half.

I would like to spare myself the effort of answering Yeats’ question in terms of his worldview – which is utterly alien to mine. And I do so all the more eagerly, since also this addition is susceptible to a lecture that is perhaps rather non-Yeatsean, but nevertheless not less imposed by the logic of his own image. On its wings the swan is carried into the skies, but with its webs it paddles in the waters - where the cold-blooded fishes reign. The skies and the waters wherein the amphibious swan is at home are thus opposed to the earth. And even though also a swan can waggle on its webs: it is man that naturally walks on the earth’s surface. Only from the surrounding waters and skies – the outer-human world – does the ‘brute blood of the air – come to invade man’s world and make him – Leda – stagger, if not fall as if (s)he were a second Eve.

Against this background the question ‘Did she put on his knowledge with his power?‘ acquires a new meaning. At first sight its seems to fit the classic opposition between man as spirit versus woman as body, which without doubt governed the (also political) conceptions of Yeats, as is evidenced by ‘on Woman’, where it is written:

May God be praised for woman

That gives up all her mind…

But in the light of that damned ‘honey of generation’, an unexpected overtone comes to accompany those ominous words. God in the shape of a swan - that is no less than the reproductive drive, that willy-nilly pursues its own goals without bothering about the poor, blind mortals abused as mere instruments. Merciless does it load a heavy burden on the shoulders of the very men and women that think to dedicate themselves to love and equally merciless does it deliver them to war, decay and death. Alongside the entire way of the Cross, poor overpowered Leda – in this lecture as well as in the ancient one: mankind – lets herself deceive through ever new chimera’s, whispering into her ears that man can pursue his own - human - goals: if not the divine ‘shape on the lap’, then at least the merger via the ‘loosening thighs’, or if need be ‘the feel of the heart beating’ – and since this is doomed to remain utterly ‘strange’ – at last: 'self-delight’. In this second lecture of ‘Leda and the swan’ no longer the sexes are opposed: the divine and beastly rape the human. Before being the metamorphosis of Mary and her dove, Leda (da Vinci’s ‘figura serpentina’) and the swan (‘the brute blood of the air’) are the metamorphosis of Eve and the serpent (‘the cold blood of the waters’). The feathered swan in the skies as the counterpart of the slimy snake in the waters. Or the cold-blooded fish: after all, just like the swan has to waggle on man’s earth, so the serpent can only snake on it.

And herein is to be found the very power of this poem and the merit of its poet. For according to the good old romantic tradition the poet, not otherwise than Leda for the swan, is only the vehicle of a wisdom that manages to edge its way through the musings of the poet. And – as is already implicit in the structure of this essay – Yeats did not succeed on his own. He is merely the last - albeit the supreme - link in a long chain of forebears, that one after another laid bare ever new coordinates wherein the constituent forces of the image come to nestle. Until they are condensed in a dynamic whole of strongly opposing forces. Which is a pinnacle that cannot be surpassed anymore. Similar highlights are the Don Giovanni of Mozart and da Ponte. Or better still: the Salome of Oscar Wilde and Richard Strauss. For the latter has in common with Yeats’ Leda that it were equally painters who paved the way.

It suffices to cast a glance on the countless Ledas painted since Michelangelo to convince oneself of that truth. Only in Yeats’ sonnet did Michelangelo’s Leda find its accomplishment. And no poet will probably ever surpass it.

© Stefan Beyst, october 2002

* cited from Cullingford.

CONSULTED TEXTS:

BEGHELLI, Chiara: 'Leonardo and the myth of Leda. Models, memories and metamorphosis of an invention', Telematic Bulletin of Art, September 1th 2001, n. 281.

CULLINGFORD, Elizabeth Butler: "Pornography and Canonicity: The Case of Yeats' `Leda and the Swan,'" in Representing Women: Law, Literature, and Feminism, ed. Susan Sage Heinzelman and Zipporah Batshaw Wiseman (Durham: Duke Univ. Press, 1994), 165-87.

HARGROVE, Nancy D. "Esthetic Distance in Yeats's 'Leda and the Swan'.", The Arizona Quarterly 39 (1983): 235-45.

HOLSTAD, Scott C.: 'Yeats's 'Leda and the Swan': Psycho-Sexual Therapy in Action, Notes on Modern Irish Literature.

WALLACE, W.E.: 'Michelangelo's Leda: the diplomatic context' in: Renaissance Studies Volume 15, Issue 4, December 2001: pp. 473-499.

read more »

The photographers at Premier Photography have over 25 years experience in the fashion, fitness and modeling business. Jamerson Brooks started his career as a model and actor. With swimwear layouts and acting roles in The Heat Of The Night. Jamerson was also a modeling agent for 6 years. As an agent he took photos of his new models to show New York and Miami agents ...

premierphoto.readywebsites.com

In the future world, one will be able to take a miraculous journey into a painting. Special high-tech computerized equipment will create a holographic space for our intelectual enjoyment. Through this program- a sound, color and light show - people will satisfy their need of painting in the future. The painter will become "a magician." But what else is painting other than magic? With several colors and a brush, a painter can create a world of forms, ideas and feelings, and you are invited to explore or travel in the artist's world of thoughts. Above this holographic space, an artificial brain will gather the thoughts and emotions of visitors through sensors and will be able to change the composition of the painting on request. The painting will live by itself like in a sort of dream room. In the future, people will evolve through knowledge and will get closer to God..." Rodica Alecsandra Miller. " Adventure in Immortality" screenplay for computer animation film, experience in art and technology, 1995.

www.sandramillersurrealism.com

Obscura Machina seeks out the relics of the past imagined scenes, and unconscious states

A collaboration of two artists, our world is inspired by the time of the great machines of the industrial revolution, the experimental spirit of the early 20th century, of Victorian clutter and curios, explorations of the mind, and objects of mystery and marvel.

Utilising both traditional and digital techniques, our images reflect our passion for the eclectic, desire for the unknown, and the lost poetry of the forgotten and abandoned.

www.obscuramachina.com.au

Beginning with first child's photos till the present -- 36 years. In the last sixteen years photography is a matter of life. He works as a photocorrespondent in Belorussian association of friendship and culture affairs with foreign countries, "Literature and Art" weekly and the national newspapers "The Soviet Byelorussia" and "The Republic" (since 1994 till the present time). Besides -- longtime cooperation with the famous theatres of the country (including Yanka Kypala National academic theatre) and a lot of accreditations, that means having a right to take photos of the most important political, cultural and sport events, participation in exhibitions. But the most important -- a great number of journalistic trips and journeys around his country -- Belarus. The country of deep forests and blue lakes, the country of the Chernobyl tragedy, the country of childhood, love, sufferings… As the result -- thousands of pictures. And you can find on this site only some of them.

read more »

From Skagen painters to Damien Hirst

On 26 January 2008 the new ARKEN is opening. The premiere exhibitions offer new light on the Skagen painters, a solo show with the bright young thing Andreas Golder and not least: A new hanging of ARKEN’s Collection, now for the first time exhibited permanently and including a unique Damien Hirst room.

At last! After 2½ years of construction ARKEN can open wide its doors to the new extension. 5,000 m2 of exhibition space will be the end result – twice as much as now, making ARKEN one of Denmark’s biggest museums. The new ARKEN will continue the course of shedding new light on the classic modern art. At the same time the focus on contemporary art will be intensified through both special exhibitions and a permanent exhibition of the museum’s collection.

read more »

Selected pictures of few seasons spent in Copenhagen. Bevar Christiania and Go to Roskilde festival. Winter, Autumn and Summer in Sjælland.

read more »

Born in 1965 in Warsaw. Studied at the Faculty of Interior Architecture in Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. In 1990 has made a diploma with distinction (work: MY PRIVATE CHAIRS). Participated in several exhibitions in Poland and abroad (solo exhibitions: HOME/1993, OBJECTS/1995, SHOWING IN A FACTORY/1997, MEBLARIUM 1/2002, OPERA GALLERY/2003). Created a lot of furniture-objects, sculptures, internal arrangements.

www.grunert.art.pl

After a decade as one of the world's most successful dance acts, Faithless's distinct sound has put them at risk of becoming dinosaurs. Thankfully No Roots doesn't rest on the laurels of former glory and delivers something quite special. Sister Bliss's shrill, semi-hard-house synth stabs are all but gone, replaced by less dated sounds and more thoughtful use of them. Tempos are lower and song structure plays a more valuable part, for No Roots is in fact only two gigantic, epic songs, with each track a progression on the previous one and clever segues leading into the next. The only song that doesn't fall into "Parts 1 & 2" is the lead single version of "Mass Destruction" tacked on the end; it's a funky, breaks-based tune with Maxi Jazz's trademark vocal (used sparingly throughout the album) over live bass and guitars. Anyone who's seen Faithless live knows how they can jam around their back catalog, making medleys and breakdowns of epic proportions: No Roots is a studio realization of that. Highlighted by "I Want More," downbeat tunes build until their climax when an uptempo number will kick in. "Sweep" is simply a 909 drum and percussion loop with synth flourishes that drops into "Miss U Less, See U More," a classic house tune that closes part one of the album. Something other than a collection of hands-in-the-air floor-fillers and downbeat songs to chill out to, No Roots should be listened to in its entirety. It's a cohesive body of work that builds and dips in all the right places. -- David Trueman read more @ amazon »

www.faithless.co.uk

BRING LOST “BILL COSBY” MUSIC TO LIFE

“The Original Jam Sessions 1969” Features Music from NBC’s “The Bill Cosby Show” and Cast of Jazz & Funk-Loving Legends from the 1960s “The New Mixes, Vol, I,” An Exciting and Eclectic Dose of Contemporary Mixes from Mix Master Mike, Cornershop, Bedrock, Herbert, Los Amigos Invisibles and Others

While Quincy Jones and Bill Cosby are today considered two of the most accomplished entertainers in America, the 52-episodes of NBC’s “The Bill Cosby Show” (1969-1971) were among their first notable television credits. Jones, as musical director, assembled a crack team of prominent jazz and funk artists to create a soundtrack and essentially left the tape recorder running during numerous informal jams. The sessions, however, ended up in the vault and were forgotten until over 30 years later when the “lost tapes” were rediscovered during an office move. Quincy Jones Music and Concord Records now present those sessions on two separate, yet equally unique and ultra-cool, recordings.

From the first notes of Quincy Jones & Bill Cosby: The Original Jam Sessions 1969 (in stores June 22), you know you are in for a quite a musical ride. Authentic interplay, vintage 1969, the heaviest musicians on the planet¾ Jimmy Smith, Milt Jackson, Les McCann, Monty Alexander, Ray Brown, Joe Sample, and Tom Scott and among them¾enjoying a fresh, loose, funk-loving romp.

Follow-up with Quincy Jones & Bill Cosby: The New Mixes, Vol. I (out July 13) and come full circle, as some of the hottest artists, DJs and producers from today’s international world of Lain, jazz, electronica, lounge and hip-hop help build a distinctive and contemporary bridge between old and new. Among the “new-mixers” are Mix Master Mike, Bedrock, Mario Caldato, Jr., Herbert, Cornershop, and Los Amigos Invisibles.

“We discovered some boxes labeled ‘Quincy, Jimmy Smith and Oscar, 1969,’ and about fell out of our chairs,” explains Marc Cazorla, executive producer for Quincy Jones Music, who along with producing partner Nancie Stern suggested the release of two separate albums. Jones quickly gave his go ahead. Cazorla explains, “A lot of people don’t really realize the impact that jazz has had on modern music, and Quincy’s always looking to turn people on to something fresh. Both he and Bill were completely supportive of the idea.”

There are two original session versions of the near-cult favorite “Hikky-Burr” on The Original Jam Sessions, one instrumental and one with Bill Cosby on vocals. The EMMY Award-nominated song (Jones’ first of four nominations; he won for “Roots”) became the theme for the NBC television show but also a hit single for Jones when he re-recorded the track for his early 1970s GRAMMY® Award-winning album, Smackwater Jack. Mix Master Mike turns it into a modern-day funk-classic with Cosby’s vocals and several choice elements from the original sessions on The New Mixes album.

During the original jam sessions, Jones would give ideas or themes to the musicians and then just let them play. It is obvious from “Hikky Burr” and all the other tracks included on The Original Jam Sessions that the jazz giants in the studio were having fun and savoring the opportunity to stretch their jazz legs. The New Mixes mirrored that same unscripted approach with artists encouraged “to take creative liberties.” The result is an irreverent nod to the past¾a recording that deftly retains the funk-loving spirit of the original music while firmly supplanting it in today’s contemporary music scene. “All of these artists were psyched to work with Jones’ music,” says Cazorla, “and Quincy really flipped when I played everything for him.”

read more @ amazon »

www.hikkyburr.com

Apparently, Nicholas Serota, director of the Tate Modern, was not prepared to let the name of Donald Judd (1928-1994) silently fade from our memories - did he not do his utmost to make the man famous in the first place? Ten years after his death - sixteen years after the last substantial exhibition - he presents a big retrospective of the work of the artist who has 'changed the course of modern sculpture''. The exhibition travels to Düsseldorf (19/06 to 05/09/04) and Basel (02/10 to 09/01/05). Heavy artillery, that makes us ask what has to be canonised here at all cost. Who is this master and what everlasting works did he leave to posterity?

BOXES

'Il faut être un homme vivant et un artiste posthume' Jean Cocteau, Le rappel à l’ordre.

From 1947 to 1953 - in the heydays of the very 'abstract expressionism' that soon will be promoted as the panacea of the Free World with a little help from the CIA* - Donald Judd studied at Art Students League in New York, the College of William and Mary and the Columbia University. Meanwhile, he is already fully active as an art critic and a painter. Already in 1957, he has his first show in the Panoramas Gallery - although from the paintings exhibited there no trace is to be found in what is announced as the 'first full retrospective'. But things are not going well with the Action Painting in New York. Andy Warhol comes to replace Jackson Pollock. Accordingly, the expressionistic gestures on Judd's canvasses are replaced with a baking tin (1961).

read more »

Wang Qingsong, 2004